Legendary Photographer Mark Seliger Shares the Stories Behind His Most Iconic Portraits

Over a career spanning 30+ years, photographer Mark Seliger has crafted more indelible portraits of iconic figures than perhaps any photographer alive. In his time with Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair, he’s trained his lens on countless legends from the worlds of music, film and politics, using unbridled creativity, nuanced technical style and the occasional wild animal to create images that have been imprinted on the collective consciousness and continue to endure decades after they were taken.

Recently he partnered with venerable auction house Christie’s and advocacy organization RAD on RADArt4Aid, a dedicated global auction to benefitting COVID-19 relief organizations around the world. Limited-edition prints of 26 of Seliger’s most memorable works are currently available for bidding, ranging from Brad Pitt to Willie Nelson to President Barack Obama (it bears noting, however, than one could bid on this auction wearing a blindfold and be guaranteed to take home something worthy of a prime spot on the wall).

“We tried to pull together imagery that we thought people would really enjoy,” says Seliger. “And we were able very quickly to connect with the subjects and say, ‘Hey, we’re going to be doing this cool auction and we’d love your participation.’ The response was overwhelming and very enthusiastic. Everybody’s doing it for the passion, for the love, for the care of the world.”

We chatted with Seliger about his process and some of the tales behind the portraits, which it also bears noting are only available until 11 a.m. on June 17th. So get on it.

InsideHook: How many of your subjects sort of bring their own ideas to the table for the shoot?

Mark Seliger: That’s a good question. I think it really varies from subject to subject, but what I’ve found is that with a musician or an artist that is not necessarily playing a character, you sort of stay in their world and in their wheelhouse. We keep it more in the key of who they are. I feel like people who are in the theater or the acting world don’t mind playing a character. It kind of takes the onus off having to play themselves. If I’m working with comedians, more often than not we will do a brainstorm about what the concept is because comedy is a very individual and personal experience. And what you think is funny may not be what they think is funny and vice versa. So it’s very much about kind of collaborating in that world.

So as an example, Jerry [Seinfeld] came to me with this idea for the cover of Rolling Stone. It was for the final episode, the finale, of Seinfeld. And his idea was that he wanted to do The Wizard of Oz as a theme, which was just awesome. I vaguely remember him saying that [the characters] were sort of symbolic to the characters of Seinfeld. He’s always said that never happened. So I believe it was probably a dream I had.

And he saw himself as the Tin Man, or was that your suggestion?

No no no, he was very specific about who was who. He didn’t have to think about that too hard. Obviously Kramer was going to be the Scarecrow. George was the Cowardly Lion, and he was the Tin Man.

Is it really true that you were riding on top of a moving SUV to capture that shot of Brad Pitt on his motorcycle?

That is true, I was. When we’re working in some commercial aspects and a lot of editorial aspects, it’s pretty low-fi. We’re not doing it by the book. That was in Humboldt County, California, up in the redwood forests, the Avenue of the Giants. The conversation that Brad and I had about the shoot was that he wanted to go to a place that had really amazing tall trees, and Humboldt was one of the most impressive places that I had seen. When we got up there, we got word that he was going to bring up a couple of his personal motorcycles, and so one of the things that we planned out was photographing him riding and the best way to do that was for me to be laying on top of an SUV.

Were you strapped in or anything?

I was not. It was on what we planned to be pretty flat ground and I was just laying on top of there shooting. I do my own stunts! I like the adventure of what we do. That’s part of the fun of my job.

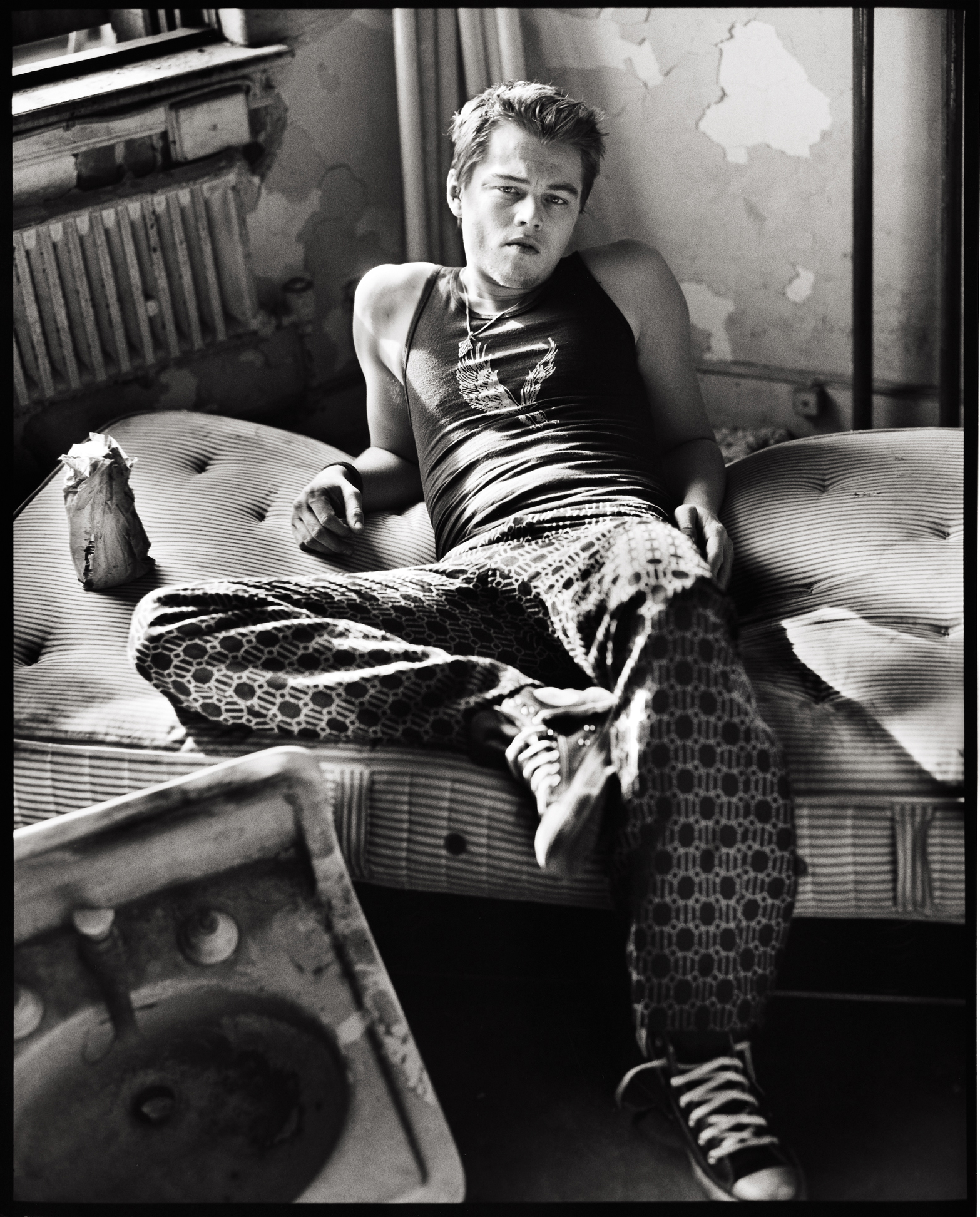

You captured Leonardo DiCaprio at such an ascendant point in his career. Titanic had come out just two years earlier and then he’d done The Man in the Iron Mask with The Beach on the way. Did you get a sense, even at that time, of, “Oh yeah, this kid is going to be a juggernaut.”?

I was a big fan of his since Gilbert Grape. When that movie came out, I actually photographed him preemptively. If you Google it, it’s “Leonardo DiCaprio making a muscle.” He was probably about 15 or 16, and he’s pushing his muscle up, he’s got arms like wires. He’s like a little kid. But you could tell this guy was a force of nature. I really felt like he was very, very unusual and very talented. I mean, there’s very few people that that were childhood actors like that, or young actors like that, that have had anywhere near the longevity and the quality. Somebody who repeatedly makes the right choices.

When he’s working, he’s creating something, and he’s there to do the best work he can. It doesn’t matter whether it’s for a magazine or whether it’s making art in any form. He believes that if he commits to doing something, that it’s going to be the best he can possibly do. That’s pretty rare and a pretty wonderful moment.

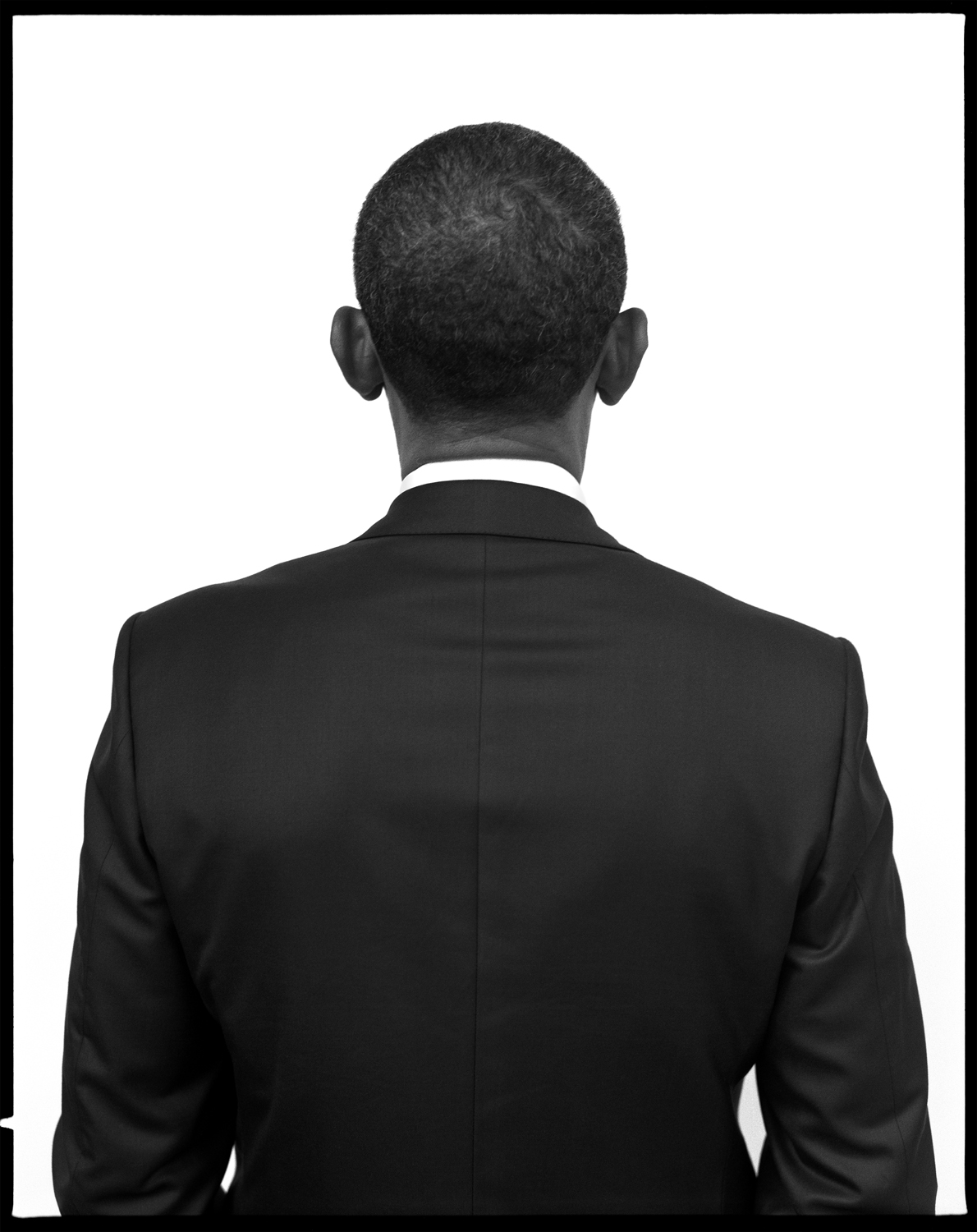

Real talk, how much do you miss Barack Obama right now?

Oh my God [laughs]. Obama, he’s such a great reflection, I think, for the world in terms of the way that he empathized. I think it’s a great reminder to all of us that it’s important for the world to embrace the changes that we’re experiencing — the good change that we’re experiencing and the obstacles that we are faced with on a daily basis — with open arms and with a lot of care and love. It’s just a very hopeful, optimistic way of working.

President Obama is one of those people, I wouldn’t say he’s not in control, but he doesn’t control what you’re doing and he’s very much committed to whatever the five or six minutes that you get with him. He’s present. We had an assignment for a cover, and when I was photographing him for the cover, we finished that pretty quickly in a couple of minutes. I was just talking to him by myself — the Rolling Stone staff and The White House staff were over by the Rose Garden just talking, not even really paying attention. So I asked him, I said, “I have this idea to do a diptych.” I had a little drawing of it. I showed him the drawing, the front and the back, and I was like, “What do you think? Can we do this really quickly?” And he’s like, “Sure. Yeah. It sounds cool.”

I was photographing the front of him and then I was photographing the back of him. And as I was photographing the back of him, I knew that was going to be pretty memorable. That was going to be the picture. I was directing him like, “Hand in the pocket. Extend your elbows out.” I was giving him very specific gestures and his body language to handle, I think I even said something like, “Okay, just chin down and smile a little bit.” And he brought it down and was like, “Why am I smiling if it’s the back of my head?” But he caught on to the idea that I was doing this pretty unusual photograph. And then the time bell went off and he goes, “Okay, Mark, that’s enough art.”

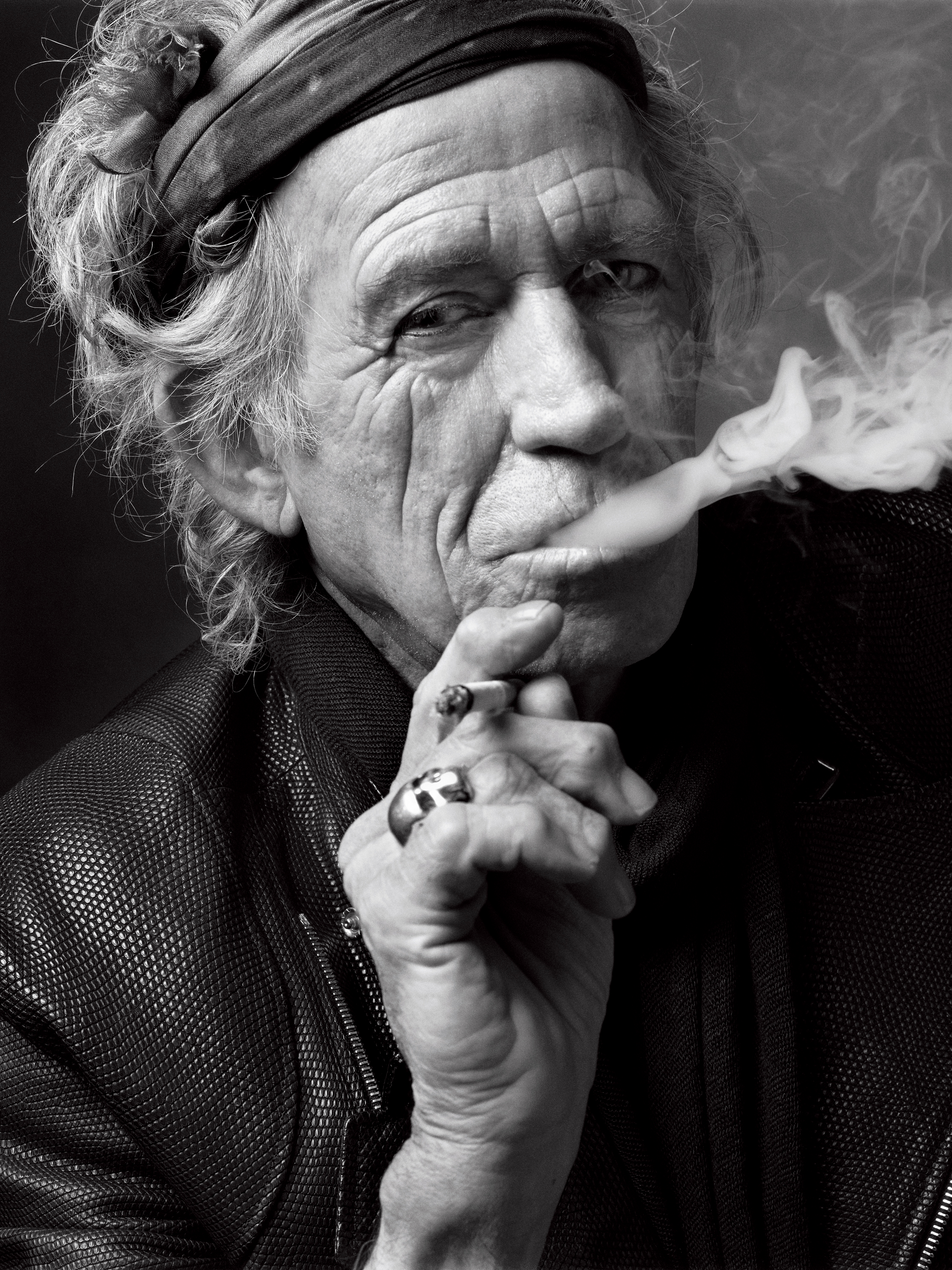

You’ve mentioned that Keith Richards is a bit of a prankster. I’d love to hear how that has manifested in your interactions with him.

If you watch any interviews with Keith Richards, he’s just a very … he’s got a little bit of the devil in him and he’s sarcastic and funny and charming at the same time. He’s got all those elements that you buzz about. So I don’t mean prankster in the strictest definition, he’s just got a wink with the way he works.

I mean, he is Keith Richards and so you get exactly what you think you’re going to get. The guy embodies rock and roll. He’s cool and slouchy and wiry and agile and laid back and funny and charming and talented. He’s got all those elements that embody rock and roll. Every line, movement of his face, they’re all the architecture of who he is. He’s just a warm spirited guy. You sit down with him and he actually connects with you. He makes it fun and he knows who he is. That’s what I was saying about a musician, you don’t have to try to go very far past the person. You just try to create the best moment with him.

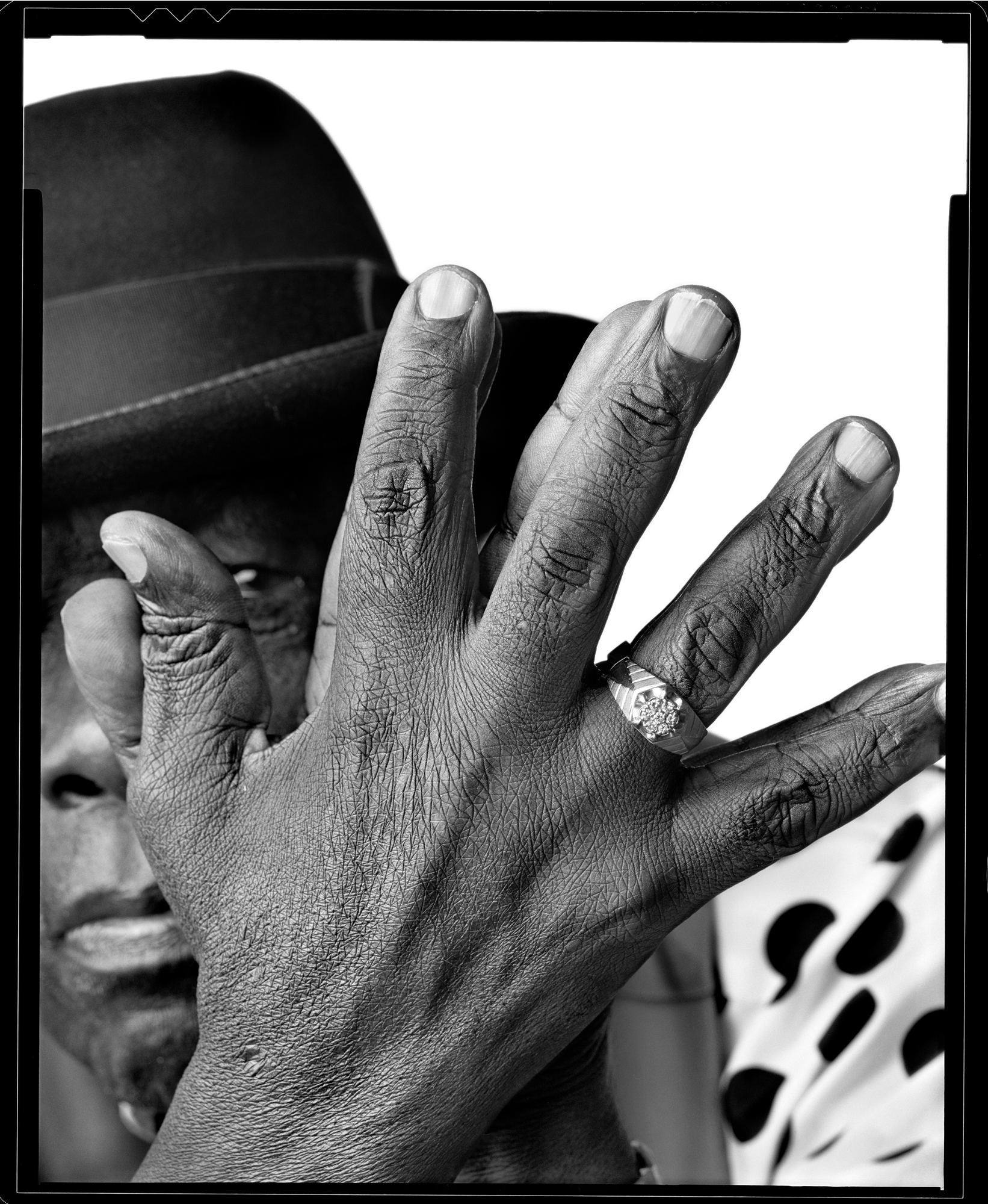

There’s a similar feeling with your portrait of John Lee Hooker. When you shot with him in 1990, the man had been recording professionally for over 40 years. He was such a living document of American blues music.

Yeah, that was a really special shoot. That shoot was actually a turning point for me, because I wasn’t full time at that moment. I was still just a hired freelancer. So John Lee Hooker was one of those moments where I was really photographing a real legend, one of my first encounters with somebody who had that relationship with legacy.

We went to his house. I mean, it was literally you drove up to John Lee Hooker’s house, parked in the driveway, knock on the door, he answers the door, you walk into his house. He’s got an La-Z-Boy chair that Bonnie Raitt had given him with a plaque on it. When I met him, he shook my hand and I remember the hand, there was a warmth. There was a lot of character to the hands and to the nails, like they had lived a life. Very seldom do you feel that. And I was like, “Wow, you have great hands.” I said that to him. And he said, “Feels like velvet, right?”

We photographed all day long and I went back to my crappy hotel near San Francisco, and I was sitting there kicking myself going, “You didn’t get the picture. The picture was of the hands!” So I called him up — I had his phone number because that’s the way he did business — and he answered the phone. I said, “Mr. Hooker, I am very sorry, but I think I might have a little bit of a problem with the film I shot. I was wondering if I could come by for 20 minutes.” There was a pause and he says, “Come over and I’ll give you 20 minutes, but you got to set up on my driveway. I just want to walk out and take the picture.” That was it. What I always pull from that is that if you didn’t get it, you got to go back and get it.

It’s a brave thing to call John Lee Hooker back and ask him for more of his time when you’ve just spent the whole day there.

You do not want to get cursed out by John Lee Hooker.

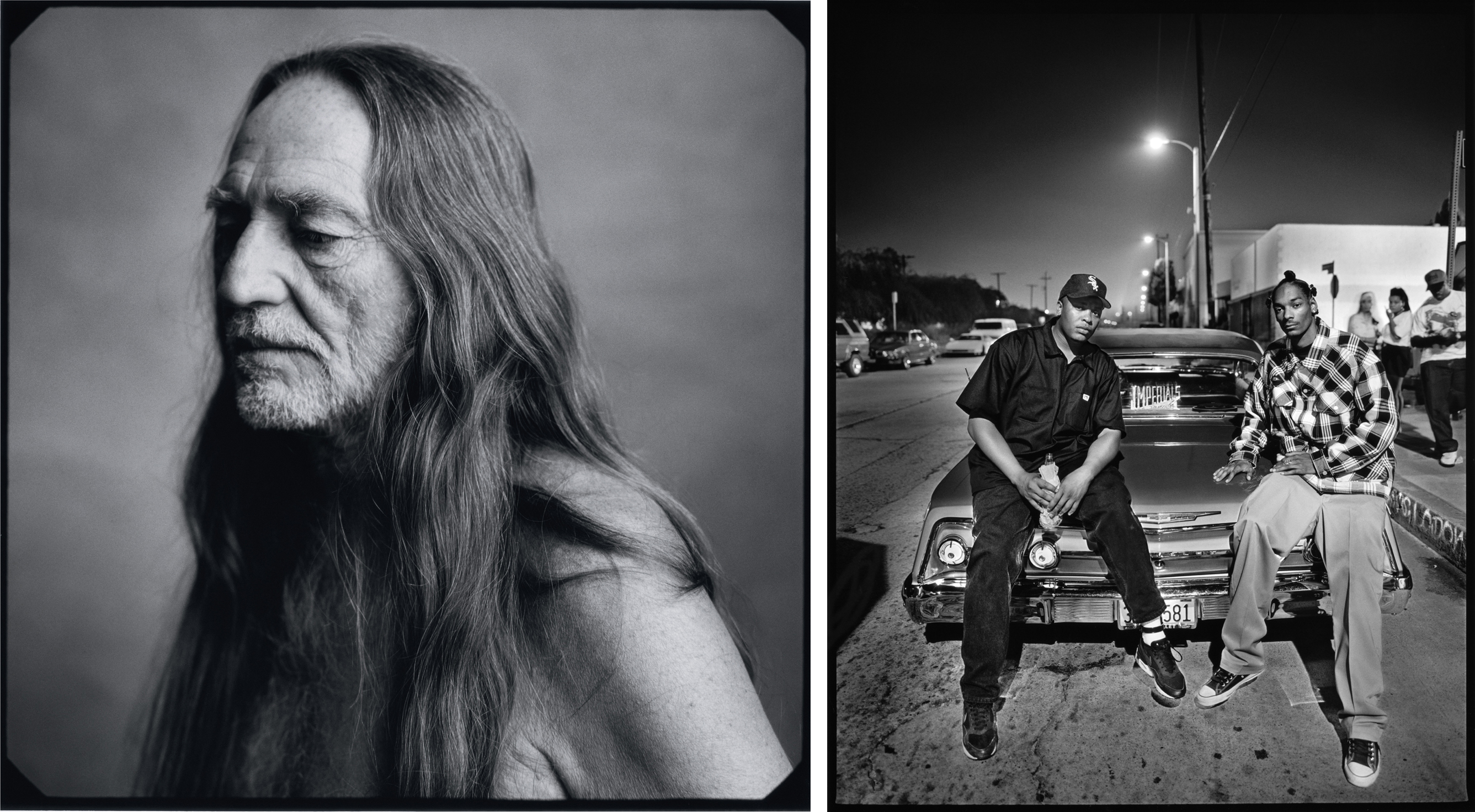

Moving on, which shoot had the bigger marijuana budget: Willie Nelson or Snoop and Dr. Dre?

Definitely Willie. I remember everybody had just come up to hang out with him on his bus, and literally when the door opened it was just a waft of weed. I immediately wanted to go to Burger King. The guy takes his cannabis very seriously.

He’s a huge advocate.

He should be. I mean, I think that Willie’s been Willie for a long time and you can’t deny the fact the guy has had nothing but love and success and being on the road exactly the way he wants to be. Willie’s a pro. There’s nothing that’s conventional about him. I mean, he’s a true outlaw in the way that he’s preserved his legacy as a musician. In a world of country where everything can be very manufactured and very calculated, he’s always done it his way. He’s a wise man and a wise ass. I could probably say the four dirtiest jokes I know I attribute to Willie Nelson for giving them to me.

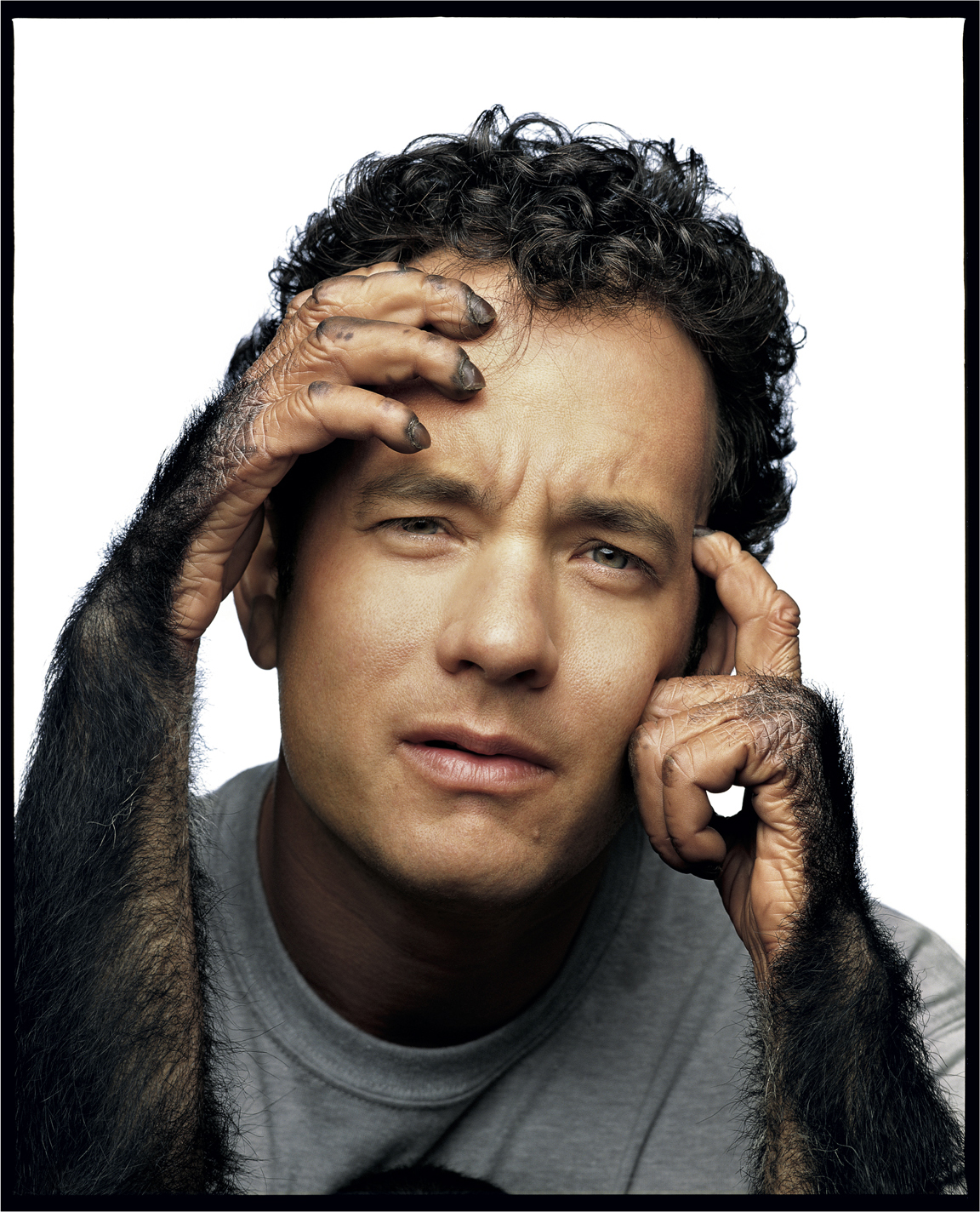

Weird question, but must be asked: How was Tom Hanks’ interaction with the monkey? They get along?

[Laughs.] Alright, so that was a little bit of a freestyling experience that was a little bit of an interpretation of Forrest Gump. I don’t know how I got there, but it was about the instinctual, bringing back our human instincts, ideas. Almost like a sense of evolution. What I loved about the chimp was that there was this interplay between the two of them, and there was some sort of an innocent behavior about the way that they reacted to each other. And that photograph just came about because when the arms of the chimp came around Tom it made a little bit of a gesture, the chimp actually did it on its own. And it was a little bit of manipulation with the hands where we just needed a finger here or there and it looked like Tom’s hands. And there was this new version of the evolution of man.

I don’t really know where the ideas come from, if they come to be sparked by watching the movie and thinking about my own life. I’m a little bit of a nutty professor. There’s certain things that make sense to me, and I feel like I related to that character a lot. There was this hopeful unawareness, I guess. You don’t want to know too much about the world, but at the same time you want to be able to take the good parts of it and give it a little bit of gravitas.

Speaking of relating things to movies, I feel like there’s this real Apocalypse Now vibe to your portrait of Kendrick Lamar. It’s similar to that shot of Marlon Brando when Martin Sheen encounters him at the end of the film. It’s very cinematic.

Kendrick is, in my opinion, one of the great poets and songwriters out there. When I got the assignment, I really dug deep into his music and some of the lyrics and the way that he engineered, and I just felt like he deserved a really, really powerful portrait and I decided to go more through lighting than concept.

There was just something about the silhouette and the quality of contrast and the reductiveness of shadow and highlight that gave it a sense of mystery and intrigue that I just loved. I don’t think I had ever done a portrait like that before. To add that much, I would say, graphic quality to it. It just worked with him. He’s very quiet. He doesn’t really engage in small talk, but he loves process. The moment that we started to work, we carved out the shoot, how we were going to do it and just started working at it, and we carved it out to where it was really cool. And every time that he saw an image that he liked, he would really encourage. He was very encouraging and grateful.

I’ve never met anybody who worked as hard as Kendrick Lamar. He did a show at the Barclays Center then went and worked in the studio all night long, he probably took a cat nap between 7:00 and 8:30 a.m. Showed up at [my] studio at 9:00 a.m. sharp and we worked until around 1:30 in the afternoon. And then he got on a bus or plane or whatever and went on to the next show. He just has a very, very insane work ethic and at the highest level as well.

Was Lenny Kravitz at all forthcoming about his fitness regimen? Whatever he was doing, I need to get on that plan.

Well, first of all, you’ve got to eat a lot of chicken breasts. And drink a lot of water. I’ve worked with Lenny for years. This was early on in working with him, he was working on his record 5 and I went to the Bahamas to shoot with him. And yeah, it was intense. He was on a very, very specific diet, exercise regime, disciplined, working in the studio all night long, sleeps when he can sleep. And then he works out and he eats on a very specific timeframe. Lenny has always been in incredible shape and he takes very, very, very good care of himself.

Regarding that image in particular, there’s something so powerful about seeing someone who’s not only known for their immense talent, but also really iconic personal style, in nothing but his birthday suit.

Well, that was after a week of shooting and I just ran out of wardrobe to photograph. “We just shot everything Lenny, we might as well just do this one in the raw, in your birthday suit.” I think at that point I had just worn him down so much in taking his picture. He was like, “Let’s just get this over with.” Lenny’s like my brother. I don’t really consider a lot of people that I’ve worked with to be personal friends, but Lenny’s always been a great friend and we’ve worked together on a lot of things. I just put out a new video for him, one of my favorite pieces that we’ve done together on the song “Ride.” To watch Lenny work in the studio and to see the way that he handles himself in terms of his connection with people and his fans, how he treats people that work with him, and work for him, he is one of a kind. He’s just a very, very soulful man.

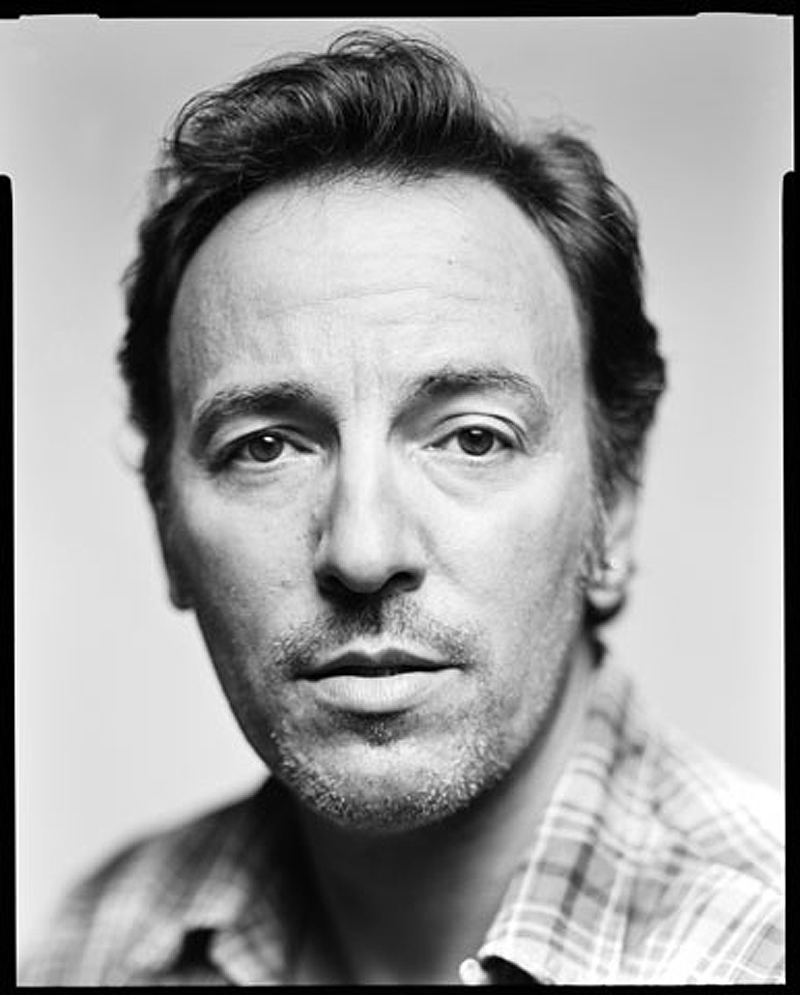

The portrait of Springsteen, it has an almost sort of tintype feel to it. How was that shot?

That was the first time I photographed Bruce. I didn’t know very much about him — I was aware of the Springsteen mania, but I hadn’t spent time with the music, I hadn’t really gotten to know the man, the songwriting, I had never seen the show. And I started to research, and I just was blown away. I got it.

I believe I did that in 1999, so he was 49. And I think I kind of put that together, like, “Okay, this is sort of like a seminal period.” I wanted to match the music with the portrait. I wanted to just be raw, and real, and honest. I wanted it to be authentic, because I really got it. I thought of him as an authentic guy. He’s the real deal.

So that was shot on a four-by-five. That’s an old school four-by-five. And the trick is that when you’re shooting a large-format picture like that, you’re dealing with complications of depth of field. I knew that I wanted his eyes, and anything on the plane of his eyes, including his mouth, to be in focus, and everything else to kind of go out of focus. And that’s very, very tricky with large format because your focus is so critical. Somebody can move, literally a sixteenth of an inch, and everything’s off. So it’s much to the credit of his own patience in that picture.

The way I approach pictures and portraits of people is like, “Okay, here’s my one time to photograph them,” without the knowledge I’ll ever photograph them again. You’re trying to treat it like “This is your chance. Don’t blow it.”

That idea sort of connects to this portrait of Kurt Cobain, because his death unfortunately followed so closely after.

I had one session with Nirvana in Melbourne, a very rushed session for Nevermind. The day before, I met with Dave Grohl and Krist [Novoselic] and I had a friendly exchange with them, and they said “What do you want us to wear?” I was like, “Look, you guys, I’m not going to tell you what to wear. It’s all cool.” I gave them some suggestions, you know, “Bring a couple of things and we’ll find the balance.” And they said, “Okay, cool. We’ll let Kurt know.”

I got a great location out in this amazing kind of Australian landscape. The van pulls up and Dave gets out, and he’s kind of laughing. And Krist kind of stumbles out, and then Kurt gets out, and he was wearing his trademark cardigan sweater and jeans, and he walks over and he starts to unbutton his cardigan. He’s wearing these big sunglasses, and he opens up this cardigan and his T-shirt says “CORPORATE MAGAZINES STILL SUCK.”

And you’re there to shoot the cover of Rolling Stone.

I’m fucking freaking out. I’m like, “Why did I open my big fat mouth? Why did I say anything?” And I’m just blaming myself, but at the same time, I was working quickly, clouds rolling, and I didn’t want to miss this incredibly saturated, beautiful blue Australian sky that all of the sudden has created itself for me. So I just kind of thought, “Okay, we’ll fix it later” or whatever.

The shoot was over in under an hour, they were on tour and I was lucky to get that much time with them. They take off and I’m just rattled. I’m like, “Oh fuck what an idiot. I’m an idiot.” I get back on the plane, and I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Australia from New York, but it’s a long ride home to put your mind to thinking about, “Okay, how did I fuck that one up?” But in the true spirit of the changing of the guard, Rolling Stone ran the cover just as it was.

So when In Utero was about to be released, I was assigned to photograph them again and I thought for sure the band would just say no. You know, like, “No, we had a terrible experience.” But much to my amazement, they were fine with me being selected.

I had an idea of kind of an answer to that previous image. I ordered three Brooks Brothers suits, the answer to that “corporate magazines still suck,” and I thought, “Well, if they don’t have a sense of humor about that, we’ll just do a straight portrait.” They all wore the suit, which was hilarious, and Kurt, you could tell he was almost like giving me a gift for not fucking up that earlier cover.

And then I had set up this picture for the three of them, which was kind of this weird diorama with the roses and the baby heads. It worked better with just him, it was really supposed to be more like a painting than it was a photograph. It was more illustrative, and that picture sat in the vault for about 25 years before we even used it. Then it became the cover of a book. But when I recall that session, I always think of it as a gift that Kurt gave me because of the … I don’t want to say necessarily respect, because I don’t know … I just think that in his way, he was saying, “I appreciate the fact that you didn’t change anything. You didn’t try to make us go in a different direction. You didn’t whine about it. You just let us be the band, the way that we are.”

It’s all about trust. That trust can either come within five minutes of the shoot or you just kind of have to ride the wave, and you don’t always get your way. My advice to young photographers when they come into the business is you’re going to fall on your face every single time in some way. You’re not going to ever walk away from something thinking “Well, that was so perfect” because you’re always going to find room for her improvement.

That’s the key word for being an artist is you’ve got to find the moments of improvement. And the element of realizing that it always works out if you do the hard work. “It will always work out” is really the philosophy that you have to have. And much credit to the artists I work with, in that a great artist inspires that. Their longevity inspires that. They’re always sharpening the pencil in a way that is true to who they are. Greatness is really about having an affinity and a devotion to your craft and to being, not a perfectionist necessarily, but just being aware of craft.

You know, there’s a constant conversation about photography, of like, “Oh, you know, the tools have changed. People are looking at imagery on a screen. How do you feel about this thing and that thing?” And I’m like, “Look, it’s all a paintbrush.” If you gave me a crayon to work with, I’d still figure it out. It’s just a paintbrush. That’s the way that you have to utilize creativity. You have to take the paintbrushes and have a curiosity about what they can do and what your imagination can do with them. If you are limited to what you have to use, then you’re not using what the most important paintbrush is: your imagination.