At the age of 22, Eva Keller started using the patch. Knowing she did not want an invasive contraceptive like an IUD or to have to remember to take a pill every day, Keller opted for a transdermal contraceptive patch, a highly effective form of birth control that can be worn on certain areas of the body.

She remained on the patch until she started to black out at random times: while taking a shower or, even worse, while at work.

“I was working at a hotel at the time, and any time I would need to bring out a case of water, I would set it down and I’d stand up and literally just black out for a second,” Keller tells InsideHook. After speaking with her doctor, Keller switched to an oral contraceptive. Now 26, Keller experiences a different set of side effects that include chronic headaches and “crazy mood swings,” both commonly associated with hormonal contraception like the pill.

Keller, who runs the food and travel blog Discovering Hidden Gems with her husband Matt, explains that part of the reason she started a travel blog is that working a full-time job can be difficult when your health is so erratic. “You never know when you’re going to wake up and have a headache all day long,” she says.

Her experience with birth control is not uncommon. Nearly two-thirds of U.S. women use some form of contraception according to a 2018 CDC report, with the oral contraceptive pill being the second most used form, just behind female sterilization. Common side effects of hormonal contraceptives include nausea, irregular bleeding, headaches, lower libido, weight gain and potential mood swings. Though rare, stroke, heart attack and blood clots are also possible, and some birth control users have noted an increase in anxiety, depression and fainting spells.

On TikTok, more and more women are sharing their experiences with birth control, and the videos have become PSAs of sorts. Users on the video-sharing app have joked about the unpredictability of the pill, which can give some users clearer skin while others are dealt lower sex drives. Other TikTok users simply brandish the knee-length, front-to-back instruction and side-effects list that’s written in minuscule fine print, pointing out that their boyfriends and men in general aren’t aware of how hormonal contraceptives can affect their partners.

It is safe to say the responsibility of contraception often falls on women. It’s widely understood that men don’t like to wear condoms, and even with a condom, an extra layer of protection like oral contraception is desirable for many women, who, in the event of pregnancy, have an even larger burden to bear. So for many sexually active women, securing birth control is a borderline instinctive action. And, worse, some men have come to expect it.

Keller recalls her husband laying down some ground rules before they were intimate: “We are not doing anything unless you’re on some form of birth control,” he told her. She admits she wasn’t interested in going on birth control to begin with because of the hormones and possible side effects, but as a non-believer in the rhythm method (estimating the likelihood of fertility based on one’s knowledge of their own menstrual cycle), the only reliable option for Keller was birth control.

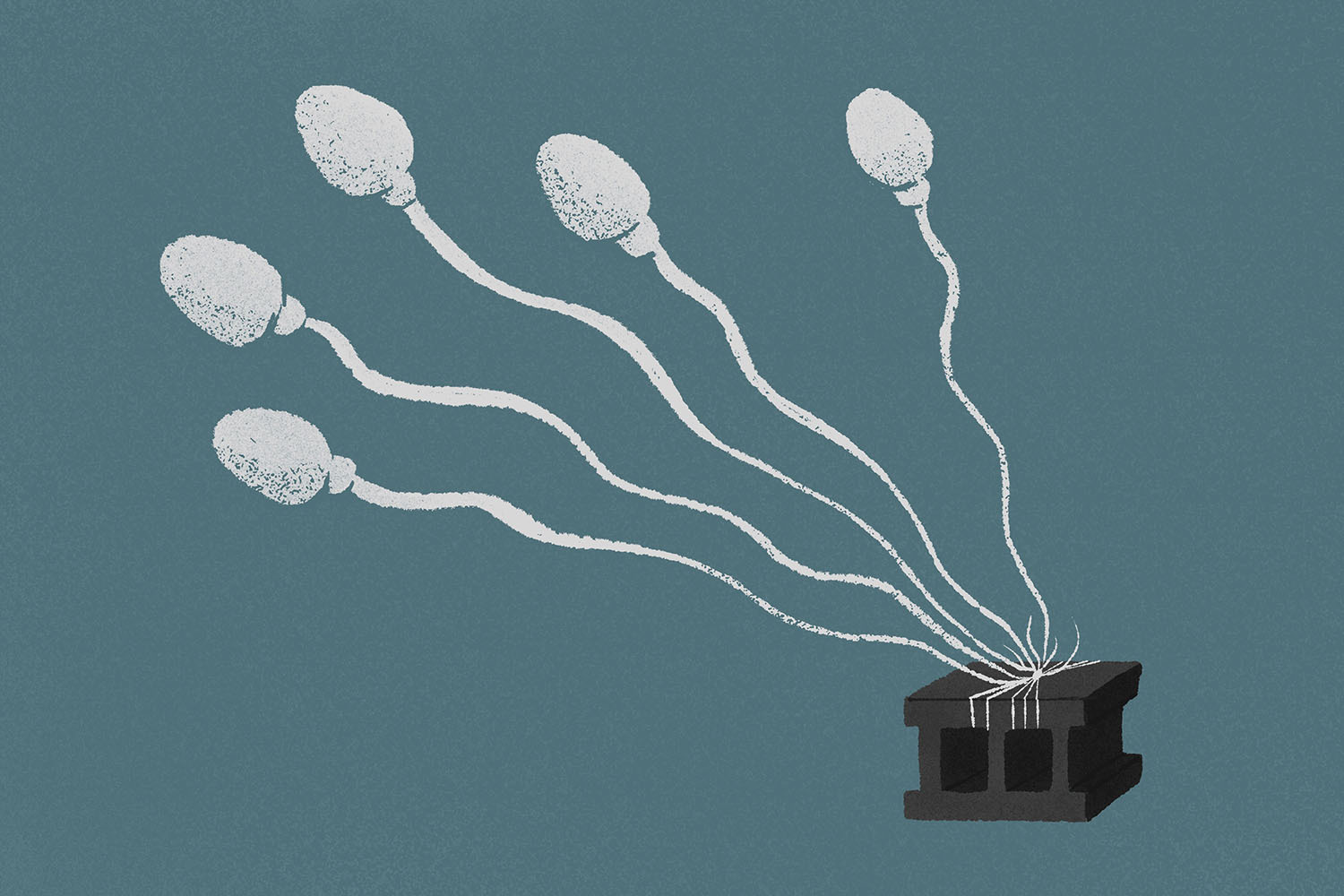

For many heterosexual couples, birth control that’s taken by the woman is the only near-foolproof, stress-reducing form of contraception, since condoms and vasectomies are the only two forms of available to men. For now, anyway. One male birth control study is currently underway and is showing promising results. It’s possible we could see the first male hormonal contraceptive on the market within the next ten years.

But one question looms large: Will men take it?

Male birth control has always felt like a pipe dream. It might be because we’ve seen male birth control trials in recent years fail for the exact reason women have been raising concerns about their own experiences: the side effects. In 2016, it was reported that a male birth control shot was found to be 96% effective, but the study had been cut short due to side effects, the most common of which were acne, increased libido, mood changes and muscle pain. The headlines made for easy viral fodder from women on the internet, who, by large, were not shocked to hear of the reported side effects. It seemed male birth control was a hopeless endeavor, and something most men would never accept as part of their lives.

The framing that men were just too wimpy to handle the side effects women have always dealt with may hold a morsel of truth, but it’s technically not true. For one, participants were instructed to report their side effects, and while 20 men did quit early due to adverse effects, more than 75 percent of participants said they would have been willing to use this method of contraception after the trial. Clearly, there were other factors at play.

Almost seven years after that study ended, The National Institutes of Health (NIH) began funding a new male birth control trial. The international study, which started in October 2018, is testing a reversible male contraceptive gel in seven sites across the U.S. and six countries around the world. The goal is to have the product be at least as effective as the birth control pill. While studies are still ongoing, the trial has some serious promise and could lead to the first male hormonal contraceptive on the market — more than half a century since birth control was approved for women.

“The study’s progressing well. If there were issues, it would be stopped along the way,” Mitchell Creinin, a family planning specialist and lead study investigator at UC Davis Health in Sacramento, one of the clinical trial sites, tells InsideHook. This method of male contraceptive is one of the few that has gotten this far in development in North America and Europe, and its progress can be attributed to the primary hormone that’s being used to prevent pregnancy, which is a relatively new one. While 20 to 30 years old, it’s still comparatively younger than the hormones widely used in birth control pills, which are 50 to 60 years old, explains Creinin.

The male contraceptive gel, called NES/T, comes in a metered dose pump and is applied once a day to the shoulders. The gel contains the progestin compound segesterone acetate (Nestorone) and testosterone, similar to already available and FDA-approved testosterone gels like AndroGel, which is a hormone replacement medication that’s absorbed through the skin. “All we’ve done is conceptually taken that testosterone gel and added in the other hormone, and that’s giving us a contraceptive,” says Creinin.

Developing male birth control is a tad more complicated than female birth control, since the female reproductive system is cyclical. For most people who have regular periods, an egg pops out every four weeks, so 13 times a year that person is susceptible to pregnancy. Female birth control uses progestin to shut the ovary down and estrogen to replace the estrogen no longer being produced by the ovary. For men, it’s a similar process. Progestin stops the testes from making sperm and hormones, and therefore testosterone is also required in the contraceptive, so men can still do all the things testosterone enables them to, like get erections.

However, men are constantly producing sperm, which represents a challenge. Women can start a pill that almost immediately stops them from ovulating and prevents them from getting pregnant, while men have “storage facilities” (aka the epididymis) full of sperm that is always being replenished.

“For hormones to work for the man, if you stop the testis from making sperm, he can still get somebody pregnant, because you still got all those sperm in the storage facility. So you have to wait for the storage facility to be empty and not be replenished by new sperm before it’s safe for him to consider that he and his partner are protected against pregnancy,” explains Creinin, who adds that it can takes three to six months for the sperm count to become low enough that the chance of pregnancy is nearly gone. The same is true for going off the contraceptive. While the testes start working again immediately, it’ll take three to six months to build up enough sperm to conceive.

Because you’re pumping the body with hormones, the gel is expected to come with side effects similar to the pill, but unlike prior studies, the NIH one is still in progress, so it can be assumed that whatever side effects have been reported aren’t cause for much concern. Additionally, like the pill, the gel must be applied every day, and the man cannot get wet for four hours, so like most contraceptives, it requires some special care.

That there’s a real chance male birth control could be on the market and perhaps even usher in a new norm for fertility and contraception is an impressive feat. “For the first time, I’d say it’s a real possibility,” says Creinin, who estimates that the male contraceptive gel currently in trial is still around five to 10 years away from hitting the market in a best-case scenario.

But again, the big question: Will men even want to take it? And, further, thinking back to that aborted 2011 study, do pharmaceutical companies have any real interest in producing it?

In the world of big pharma, there has not been much interest in male birth control, mainly because larger pharmaceutical companies can make more money off of cancer drugs and immunotherapy. But Creinin believes male birth control is going to be something that smaller companies take interest in and will bring to the market. “This isn’t ever going to make money like a cancer drug or an immunologic, just like contraceptives don’t. I think there will be smaller companies that are focused in this area that’ll bring it to market and serve a lot of good,” he says.

As for whether men have any desire to be on birth control, surveys offer conflicting information. Some say men are reluctant while others say the opposite, but Creinin is in direct contact with the couples and men involved in the study, and he says they know it’s time to start shouldering some of the responsibility.

“The couples really are stepping up. There are men who are part of it who are in a relationship where they say they want to be on birth control because they know it’s just as important. Their partner has been the one burdened with this for years and years and years, and it’s definitely their turn.”

Still, if male birth control comes to fruition, that doesn’t mean women will start burning their pill packs — it just means the responsibility will become more balanced. “If we were to look in the magic ball 20 years from now, I think you’re going to have couples where just the woman is using a method, couples where just the man is using it. And I think there’ll be a lot of couples where both are using something,” adds Creinin.

Unless, of course, men start taking more drastic measures.

When Keller’s husband Matt saw how her birth control had been affecting her, he decided to get a vasectomy. It was a fairly easy decision for Matt, who already has two grown children from a previous marriage; plus he and Eva had always been adamant about not wanting children. “Watching her go through several years of pain and weight gain from birth control, I figured I could bear a week or two of discomfort if it would mean she would never have to experience the birth control side effects again,” he tells InsideHook.

Despite the fact that it’s a relatively safe procedure, and one that can even be reversed, only one in 10 men in the United States get a vasectomy, which is half the rate of men in Canada and the United Kingdom, according to a 2015 report by the United Nations. Female sterilization — getting her tubes tied, so to speak — in the U.S. is also twice as prevalent as vasectomies, according to the same report. And as mentioned above, female sterilization is the most used form of contraception in the U.S., with 18.6 percent of women using it according to the CDC, compared to just 5.9 percent of women who rely on male sterilization. In 2019, the New York Times posed the question: Why don’t more American men get vasectomies? “It’s a blend of cost, misconceptions and fears about the procedure, and cultural expectations about what truly defines a man,” the Times wrote, noting that most U.S. men “rely on their female partners to prevent pregnancy.”

Of course, a vasectomy might not be an ideal choice for younger men who are not yet sure they’ll want to have children in the future, but it’s shocking that vasectomies are not more prominent in older men and for couples who are done having children.

“I really think a lot more men should explore vasectomies,” says Alice Pelton, CEO and Founder of the UK-based platform The Lowdown, a first-of-its-kind review platform for contraceptives that hosts more than 4,000 user reviews on every contraceptive method and brand available. “I know it might be expensive in the U.S., but if you’re finished having kids, there is no reason, really, why you shouldn’t get a vasectomy. It’s very low-risk, non-hormonal, with very few side effects, and if you think about the cost benefit of having a vasectomy at the age of 45, that means you guys, as a couple, are sorted for the rest of your lives.”

The lack of male sterilization in the U.S. is a clear indication that, again, fertility is largely looked at as a woman’s issue. But men like Matt think it’s time men take ownership of their fertility and help their partners out. “If you truly love your partner and knew you never had any intentions of having a baby, wouldn’t it be worth it to spare her the ongoing side effects and pain by manning up?”

Regardless of whether you’ll be first in line for the male contraceptive gel, you’re thinking of getting a vasectomy or neither, what your birth control-taking partner wants you to know is that being on birth control is not a simple, stress-free endeavor. And while there are limited options for men when it comes to contraception, there are still things you can do to ease her burden.

“I think that men just need to be as invested in it as we are. Pay attention to it,” says Keller, who told her husband that if she has to remember to take a pill every single day, then he should try to remind her to take it every day. “Because if you forget about it, how can you expect me not to forget about it? If you’re expecting someone to do this every single day, you should hold yourself to that same standard.”

At the very least, be mindful of what your partner could be going through. “Part of The Lowdown’s success is it makes women feel validated and listened to, and I think we need to stop ignoring and shutting women down for sharing their thoughts and saying it’s shit,” says Pelton. “So I think just from a partner perspective, the support and sympathy is much appreciated, I’m sure, by most women.”

Also, stop making women feel guilty about using condoms. “If your partner doesn’t get on with hormones and she doesn’t want an IUD, there will be times in your life where you have to use condoms, and being open and happy to do that and not making a woman feel guilty that you have to use condoms is genuinely something I would encourage men to think,” Pelton adds.

Ultimately, the point of male birth control is to not only relieve some of the burden on women, but to prompt more men to take agency over their role in reproduction, which is admittedly difficult when there are so few options. But as we hopefully see birth control for men become a reality, additional opportunities will arise for men to safeguard themselves from a potentially life-changing consequence.

“It’s about giving people control over fertility. Remember, unfortunately, fertility is an automatic on. The default for women is you’ll get pregnant. Or as the man, you will cause a pregnancy,” says Creinin. “Well, wouldn’t it be great if the default was the other way around, and then you could just turn it on when you do want to have a pregnancy occur? And that’s what contraception is about: it’s about giving you that control, so you get to decide, [it’s about] trying to change that default.”

In recent history, “that default” has allowed men to abnegate their role in preventing a pregnancy almost entirely. Will things change if and when a male contraceptive finally arrives? In a logical world, they would. Hopefully by then we’re living in one.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.