Whether it’s the Louvre theft that opens up the acclaimed series Lupin or the real-life theft of multiple paintings at the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum, there’s something about art heists that gets our attention. Perhaps it has to do with the long history of the objects being purloined; maybe it connects to the efforts of investigators to determine what, exactly, happened. Either way, we have an appetite for it.

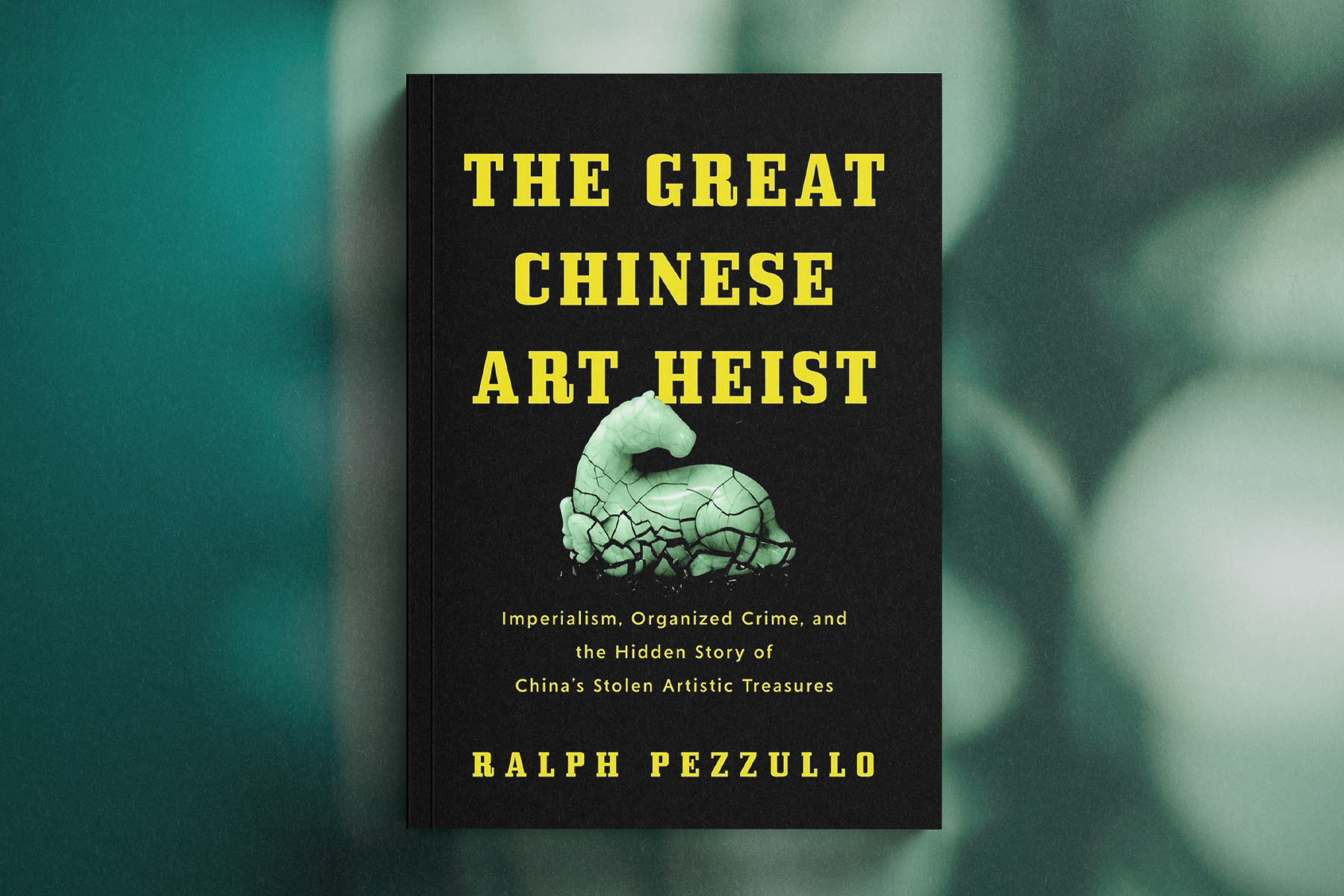

In his new book, journalist and podcast host Ralph Pezzullo chronicles a number of heists that took place all over Europe and focused on artifacts from China. The Great Chinese Art Heist: Imperialism, Organized Crime, and the Hidden Story of China’s Stolen Artistic Treasures explores both the daring thefts themselves and the centuries of history that led up to these thefts.

In this excerpt, Pezzulo describes the history of the Château de Fontainebleau — a UNESCO World Heritage Site beloved by Napoleon Bonaparte, among others — and reveals how it became a crime scene centuries after Napoleon walked its halls.

“Revenge is an act of passion; vengeance of injustice. Injuries are revenged; crimes are avenged.”

—Samuel Johnson

More than a century after the Boxer Rebellion in China, the museum break-ins in Europe didn’t end with the arrests of the Rathkeale Rovers, those Irish social outcasts who had most likely never set foot in a Bund or a proper British club.

Instead, the suspicious pattern of robberies was only getting started. A third target was the Chinese Museum in the world-famous Château de Fontainebleau 50 kilometers (c. 31 miles) southwest of Paris.

This was the second time in three years that thieves broke into a royal European residence. As dramatic as the 2012 break-in at the Drottningholm Palace had been, the robbery at Château de Fontainebleau was even more audacious. After all, the Château de Fontainebleau was one of the most famous monuments in France and a popular site for tourists worldwide. The château had been the residence of French monarchs from Louis VII, who lived there in 1137, to Napoleon III. Napoleon Bonaparte called it a “true home of kings, house of centuries.”

Like the Drottningholm Palace in Sweden, the Château de Fontainebleau is a UNESCO World Heritage Site celebrated for its rich architectural framework as well as its exceptional collections of paintings, sculptures, and art objects, ranging from the 6th to the 19th century.

Surrounded by a vast park and adjacent to the lush forest of Fontainebleau, the palace displays elements of medieval, Renaissance, and classical styles due to the many additions commissioned over the years by monarchs and their wives. Both in its architecture and interior decorations it represents the meeting of Italian art and the French tradition.

Between the hours of 2:00 and 3:00 on the morning of July 6, 1809, French troops under the orders of Napoleon scaled the walls of the gardens of the Quirinal Palace in Rome and penetrated into the part of the palace occupied by papal servants. After an hour of violent skirmishes with the Swiss Guards, they arrested Pope Pius VII, and spirited him away in the night to Savona, near Genoa, and then through a difficult journey through the Alps to Fontainebleau, where the pontiff was held captive in the former Queen-Mother’s apartment. He would remain imprisoned there for the next two years.

The kidnapping was the climax of the combative relationship between the global leader of the Catholic Church and the brash emperor, fighting over control of Europe.

On January 25, 1813, Emperor Napoleon I secured a concordat from Pius VII, a “series of articles to serve as a basis for a definitive arrangement” between the two rulers. Pius VII was only released from his golden jail at Château de Fontainebleau the following year, on January 23, 1814, when France was invaded by the allied powers, and the Empire was being shaken to its core.

During his disastrous French Campaign of 1814, Napoleon’s army held out against the allies of the Sixth Coalition—Austria, Prussia, Russia, and other states in Germany—but was ultimately overpowered. On the 30th of March, Paris capitulated. Upon hearing the news, Napoleon fled to Fontainebleau. The historic château would serve as the stage for the fall of his regime.

Napoleon spent the last days of his reign at Fontainebleau, before abdicating on April 4, 1814. In his memoirs, written in exile on the island of Saint Helena, he wrote of Fontainebleau: “Perhaps it was not a rigorously architectural palace, but it was certainly a place of residence well thought out and perfectly suitable. It was certainly the most comfortable and happily situated palace in Europe.”

His nephew, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (better known as Napoleon III, elected France’s first president in 1848 and elevated to emperor of France in 1854), resumed the custom of long stays at Fontainebleau, particularly during the summer. Many of the historic rooms, such as the Gallery of Deer, were restored to something like their original appearance, while the private apartments were redecorated to suit his tastes of those of his strong-willed wife, Empress Eugénie.

Napoleon III was the emperor of France when France and England sent a military expedition to China in what became known as the Second Opium War. And he was the leader of France when Yuanmingyuan (the Old Summer Palace) was looted and burned to the ground.

He obviously didn’t heed the advice of his uncle, who famously had said, “Let China sleep. For when she wakes, the world will tremble.”

Perhaps he was prophesying the sack of the Old Summer Palace.

One French soldier who witnessed the event tried to put into words the material significance of the event in a letter to his father:

I take up the pen, my good father, but do I know that I am going to tell you? I am amazed, stunned, stunned by what I saw. The Arabian Nights are for me a perfectly truthful thing now. I walked for almost two days on more than 30 million francs of silks, jewels, porcelain, bronzes, sculp- tures, treasures in short! I don’t think we’ve seen anything like this since the barbarians sacked Rome.

Contemporary poet Wang Shangchen tried to capture the emotional impact of the destruction of the palace in his poem “Song of Yearning”:

Barbaric destruction of symbolic retribution—the razing of the Yuanming Yuan.

Hot Indian deserts exhale poisonous miasma, roast worms of sandy gold;

Black crows tear flesh from the bones of corpses, peck at the fat, dripping blood;

Blood red poppies spring up, for all this, they make a paste of yearning.

Greenish smoke arises when paste is pounded to pieces, it drains gold and money out of the country.

The vitality of a neighborhood disappears daily; the celestial mists become the sky of yearning . . .

Following the sack of the Old Summer Palace, French officers presented a large cache of treasures from the palace to Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie. Initially displayed at the Tuileries Palace in Paris, they were moved to Fontainebleau in 1863. Treasures from the Yuanmingyuan — many dating from the Qianlong period (1736–1795) including jades, cloisonné, lacquer, textiles, and objects in gold as well as bronze — filled a suite of three rooms at Fontainebleau, which Empress Eugénie turned into the Musée Chinois (Chinese Museum).

Located on the ground floor of the Gros Pavillon near the pond, the rooms that made up the Musée Chinois were among the last decorated within the château while it was still an imperial residence. In 1867, the Empress Eugénie — a woman known for her championing of authoritarian and clerical policies — had the rooms remade to display her personal collection of Asian art, which included gifts given to her and her husband by a delegation sent by the King of Siam in 1861 and crates of loot taken from the Old Summer Palace and sent to her by General Charles Cousin-Montauban. The first shipment arrived in February 1861. The entire collection numbered some 800 objects, with 300 coming from the sack of the Old Summer Palace.

“The gifts given at that time constitute the embryo of the imperial collection,” said Jean-François Hébert, director of the Château de Fontainebleau. He specified that the collection grew quickly due to the contribution of works from the Mobilier National of the French Ministry of Culture, acquisitions made on the Paris antiques market, and further shipments from the French expeditionary force that sacked the Old Summer Palace in Beijing.

The objects displayed in the antechamber include two royal litters or palanquins: one designed to carry a king and the other—complete with curtains—to transport a queen. Inside the two salons of the museum—which was recently renamed Empress Eugénie’s Chinese Museum—some walls are covered with lacquered wood panels in black and gold, taken from 17th century Chinese screens. In the corners stand tall matching wooden cases to display antique porcelain vases. Other objects on display include a Tibetan stupa, or hemispheric structure, containing a brass Buddha taken from the Summer Palace; and a royal crown given to Napoleon III by the King of Siam.

The Chinese rooms house the Empress’s original collection of jades, gold coins, cloisonné, lacquer, and textiles. One of the most striking displays at Fontainebleau is a set of five ritual vessels of blue and gold cloisonné. They are pictured in the museum catalog resting on a set of five red lac- quered stools against a background of French chandeliers. Also pictured is the above blue and gold cloisonné “chimera” (a mythical animal with a lion’s body and dragon’s head) and an elegantly embossed pair of bronze bells—both of which were taken from the Old Summer Palace.

Empress Eugénie — who was the daughter of Spanish nobility and known as a style icon of her time — never intended for the Chinese rooms to be a museum or public exhibition space. She had the rooms decorated by palace architect Alexis Paccard — who had also worked on the Louvre — to be used as a private space where she could entertain guests and friends. That’s why the drawing room included a billiard table and a mechanical piano.

The whole suite was inaugurated by the empress on the 14th of June 1863, with a grand party attended by the crème of French society.

The Bookstore Is Alive and Well in NYC. Here Are Our Favorites.

Find your next great read hereOver a hundred and fifty years later, shortly before 6:00 a.m. on Sunday, March 1, 2015, thieves pried through the garden doors and entered what was then called the Musée Chinois. The museum was one of the most secure areas of the entire château and armed with alarms and security cameras. “It was a space,” said museum president Jean- François Hébert, “that was often closed to the public, very intimate, very atypical, with its large screens lacquered with gold.”

The thieves then shattered the glass of three display cases. They seemed to know exactly what they wanted. Working fast, they stole fifteen Chinese artifacts in a mere seven minutes. The objects stolen were called “priceless,” according to French authorities.

Before the thieves left, they sprayed everything with a fire extinguisher to remove any trace of fingerprints. And they had fled the grounds of Fontainebleau by the time the police and security personnel arrived.

Among the items they took with them were twenty gold coins from China and the kingdom of Siam, and also a crown of the King of Siam given to Emperor Napoleon III during the king’s official visit to France in 1861, an enamel piece that dates from the reign of Emperor Qianlong in the 17th century, and a Tibetan mandala.

Because of the theft and the damage it caused, officials closed the museum until it could be repaired.

Jean-François Hébert, who ran the Fontainebleau castle, called the break-in a “very big shock and trauma.”

“We think they [the thieves] were very determined, knew exactly what they were looking for and worked in a very professional manner,” added Hébert. “The objects they took were among the most beautiful pieces in the museum,” he was quoted as saying on the BBC.

French culture minister Fleur Pellerin said in a statement, “The police forces, and in particular the Central Office for the Fight against Trafficking in Cultural Property (OCBC), the Ministry of Culture and Communication and the Château de Fontainebleau are doing everything possible to ensure that these objects, which are perfectly identified, find their place in the national collections as quickly as possible.”

As in past thefts of ancient Chinese artifacts, the thieves seemed to snatch items from a list, ignoring paintings and furniture that were considered more valuable. They included some of the masterworks of Renaissance Europe, including Joos van Cleve’s life-sized painting of François I, Two Ladies Bathing from the first quarter of the 17th century, and masterpieces by French masters Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres and Pierre-Auguste Pichon. Also spared were a gallery of portraits of members of Napoleon’s family, medals, and decorations, several costumes worn during Napoleon’s coronation as Emperor, a gold leaf from the crown he wore during the coronation, and a large collection of souvenirs from his military campaigns.

“The museum was robbed, and Chinese objects were taken. The investigation makes us think that they just wanted to steal only Chinese objects,” explained one French inspector.

The above is excerpted from The Great Chinese Art Heist: Imperialism, Organized Crime, and the Hidden Story of China’s Stolen Artistic Treasures by Ralph Pezzullo, published by Pegasus Books.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.