An ambitious new study is trying to understand the genetic changes that occur at extreme altitudes by testing people who climb Mount Everest —and their twins.

Willie Benegas and Matt Moniz climbed Everest together last May, collecting blood samples along the way. At the same time, Moniz’s fraternal twin, Kaylee, and Benegas’ identical twin, Damian, provided blood samples from their homes at or near sea level.

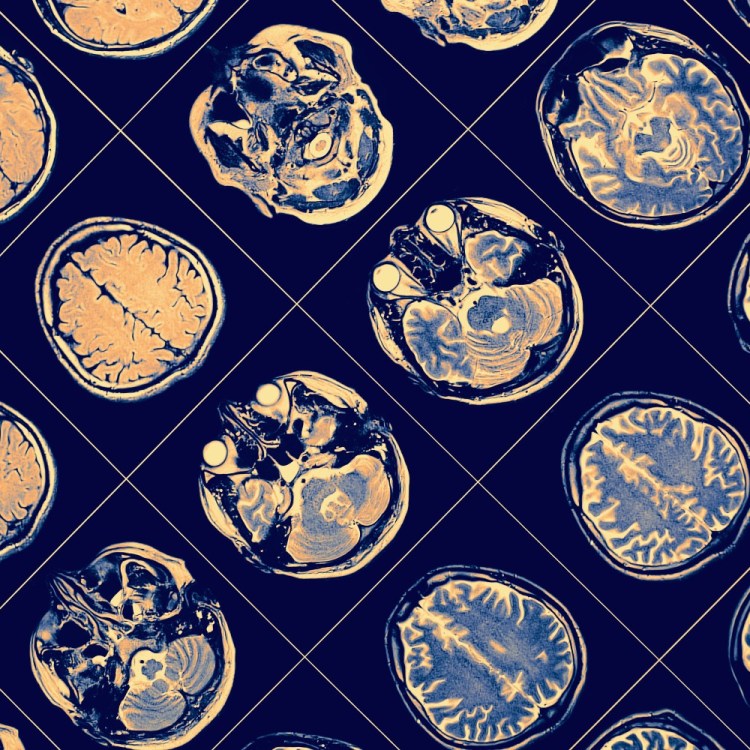

From these samples, Dr. Christopher E. Mason, a geneticist at Weill Cornell Medicine’s Department of Physiology and Biophysics, will extract DNA, RNA and plasma, otherwise known as the components needed to document each person’s genetic code. According to Outside Online, this code determines how someone’s body makes cells and how those cells respond and adapt to the environment.

“We know that time spent at high elevation will, for example, cause the body to produce more red blood cells to carry more oxygen,” said Mason to Outside Online. “What we don’t know is what’s happening at the detailed molecular level—which genes are creating that adaptation, which genes are responding to that stress, which genes are activated specifically when you climb the world’s tallest mountain?”

Mason is previously known for the 2017 NASA Twins Study, where he compared the genetic code of astronaut Scott Kelly, after he spent one year living on the International Space Station, to the genetic code of Kelly’s twin brother, Mark, an astronaut who remained on Earth. For the Everest study, Mason wants to learn about the climbers’ microbiomes, or the bacteria, fungi, viruses, and single-celled organisms that live in and around the human body, and how they interact with the body while on the mountain.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.