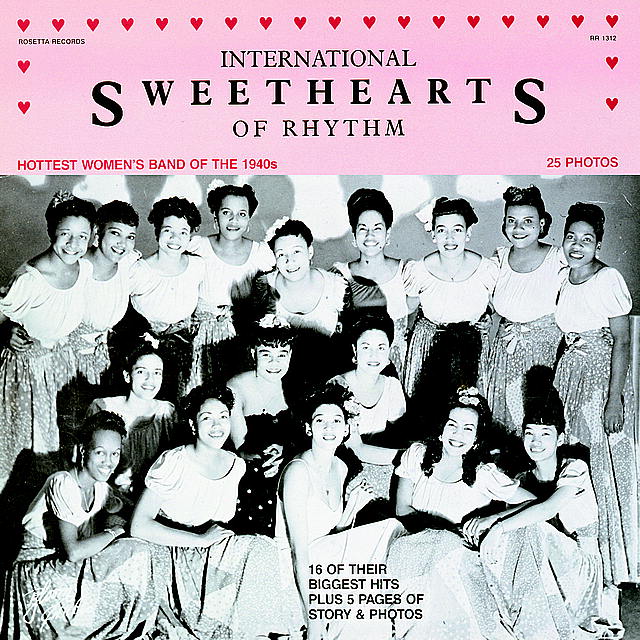

The era of jazz and swing bands in the middle of the 20th century is generally thought of as one dominated by the work of male musicians. But a new in-depth report from Megan Mayhew Bergman at The Guardian upends this preconception. It’s an exploration of the long and storied career of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm — an all-female multiracial swing band that challenged the stereotypes of the day.

The article makes a convincing case for the group’s success during their time as an active group:

The International Sweethearts broke attendance records at places such as Washington DC’s Howard Theatre, Harlem’s Apollo Theater, Cincinnati’s Cotton Club and the Riviera in St Louis. They played in the same venues as Count Basie and Dizzy Gillespie, were considered some of the most talented musicians of their day and toured France and Germany as a USO act in 1945.

Bergman talked with one of the group’s surviving members, Rosalind Cron, who played several instruments and is now 95. Cron argues that the racism and sexism of the age prevented the group from being recognized in musical histories to the extent that they should have been.

That’s changed more recently: Bergman’s article explores a few jazz histories which have sought to give the group their due. And if you look closely enough, you can see other places where the legacy of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm has entered the spotlight.

Playwright and actress Regina Taylor drew on the experiences of a number of bands, including the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, for her play Oo-Bla-Dee, which was first produced in 1999 and continues to have acclaimed productions to this day.

In an interview, Taylor traced her own interest in all-female bands to a conversation with a friend at a time when Taylor was unfamiliar with that element of musical history. Taylor was intrigued and sought out more information, including using the resources available at New York’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

“Some were noted, some were footnotes, some I would find out through word of mouth, some were recorded, some were not, some you had descriptions of their music,” Taylor recalled in an interview with Hollywood Soapbox. “I was going, oh, these women have been erased.”

But with efforts like those of Bergman and Taylor, that erasure is steadily being undone, with countless stories left to be told.

Subscribe here for our free daily newsletter.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.