When we sit down to read a book or watch a movie dealing with murder, there’s typically a tacit contract between the text and the reader that by the time it all ends, we’ll know who the killer is.

But that’s the fictional world. In the real one, we’re often left with more questions than answers.

It’s that grey area that permeates the new five-part docuseries Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children, which premiered Sunday on HBO.

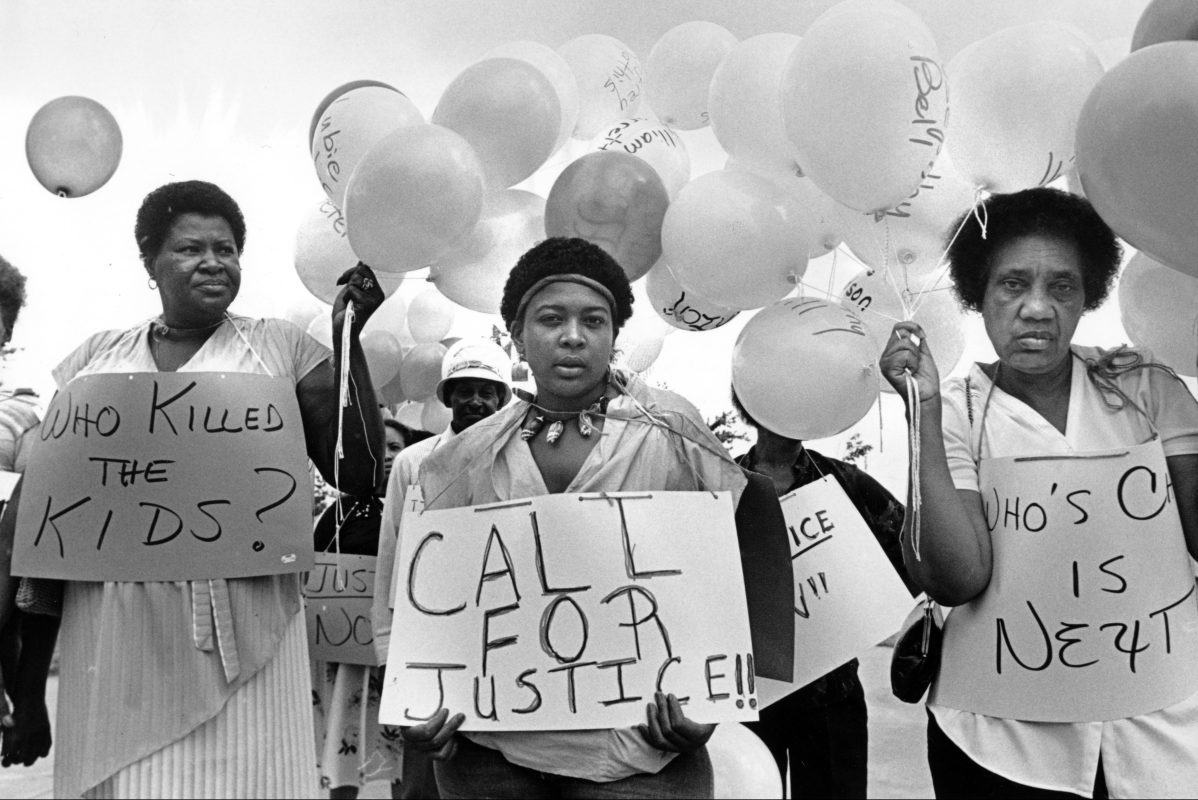

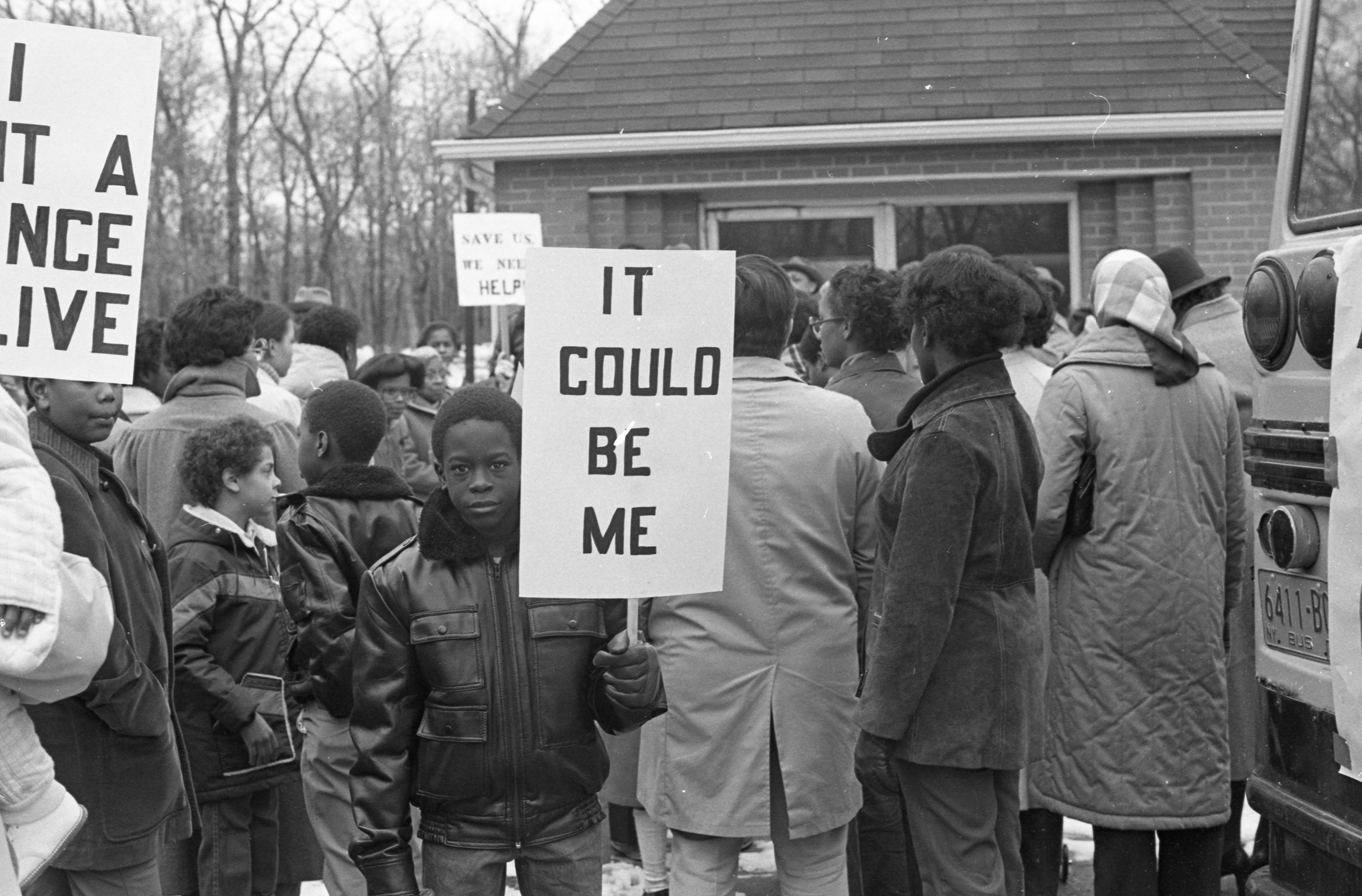

If you watched Mindhunter or listened to Payne Lindsey’s popular podcast Atlanta Monster, then you’re already aware that at least 30 African-American children and young adults were murdered or abducted in Atlanta between 1979 and 1981. The tragedy was only compounded when, in a rush to officially shut down the case, many of those crimes were then pinned on a 23-year-old named Wayne Williams, who was convicted despite a lack of hard evidence.

Executive produced and directed by award-winning filmmakers Sam Pollard, Maro Chermayeff, Jeff Dupre and Joshua Bennett for Show of Force, Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered highlights how race, inequality, privilege, fear and the history of the South all played a role in what happened in Atlanta while ultimately leaving it up to the viewer to decide who was right and who was wrong.

“We’re not trying to solve a case,” Chermayeff tells InsideHook. “We’re not investigators who are saying, ‘Oh, at the end of the series we’re going to tell you.’ But it’s really important to look at some of the choices and some of the really, truly unfair things that have happened in our country to understand how to make changes. There were a lot of elements to this story that people were still wanting to sweep under the rug, and we hope that we’re part of having people look at it again.”

Though there are countless interviews with witnesses, prosecutors, detectives, politicians, journalists and even Williams himself, the primary way Chermayeff and her co-directors get viewers to re-examine the case is through the eyes of the victims’ families.

“For them, I think it feels like yesterday,” Chermayeff says. “When you lose your child, I don’t know how different you’d feel 40 years later. Things have changed, but they still had very open wounds and they wanted to talk and find a way not only to bring attention to the issue and shine a light on what had happened, but to feel that something was being done and something was being said about their kids.”

For the filmmakers, that wasn’t a task to be taken lightly.

“For some of [the families], it was the first time and opportunity to open themselves up, to talk about the pain and the suffering they had to deal with when they lost a loved one,” Pollard tells InsideHook. “It’s emotionally wearing on them and it’s emotionally wearing on us as the filmmakers. We want to be respectful and mindful in telling these stories and respectful of the people that we’re interviewing. That’s a heavy weight to have to carry, but it’s a responsibility I take very seriously.”

Although they took place at the prison where he is currently serving a life sentence, their interviews with Williams, who has always maintained his innocence, were slightly easier.

“We talked to Wayne constantly, probably 20-something times,” Chermayeff says. “Wayne is just Wayne. He’s his own worst enemy in terms of his desire to control the situation or control a story or drive the narrative. What we noted is consistently Wayne has been saying the same thing and had the same position for 40 years. He did not do this. He did not have anything to do with this. We were struck by that and felt responsible to show the fact that Wayne’s position on things hasn’t changed.”

Because of Williams’s unchanging stance, the added attention from podcasts and shows or a combination of other factors, Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms announced the city would be reviewing its investigation of the murders while Chermayeff and Pollard were shooting.

“We did not know that was coming,” Chermayeff says. “We had been in contact with the mayor’s office and the chief of police, but we were already shooting. It was a pretty bold move for them. They don’t consider that they’ve opened a closed case. They’re reinvestigating and re-looking at the evidence. Nevertheless, it is interpreted by the community as, ‘This is not a case in which the book is closed anymore. Let’s open the book.’ It was a brave move by the mayor.”

Pollard adds: “It was one of these perfect things that happened while we were down there. Quite honestly, as documentary filmmakers, we couldn’t ask for anything better to happen.”

With the case now back in the spotlight, it’s more important than ever to remember that the circumstances surrounding the Atlanta child murders are still relevant in 2020.

“This was a horrific time in Atlanta,” Pollard says. “Never forget that the experience of these young African-American kids was a tragic one. And try to understand that the issues of race and class that were present then still exist in America even today.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.