I was drinking a Negroni at a bar called Longfellow in the Cincinnati neighborhood of Over-the-Rhine when Governor Mike DeWine’s order came through. It was Sunday, March 15, when he announced that all restaurants and bars in the state of Ohio would close to the public by 9 p.m. We all knew it was coming. We just didn’t know it would be so soon. Just like that, thousands of bartenders, bussers and servers throughout the state were unemployed. Just like that, the places where we gather and talk and drink and comfort one another through times of trouble were gone.

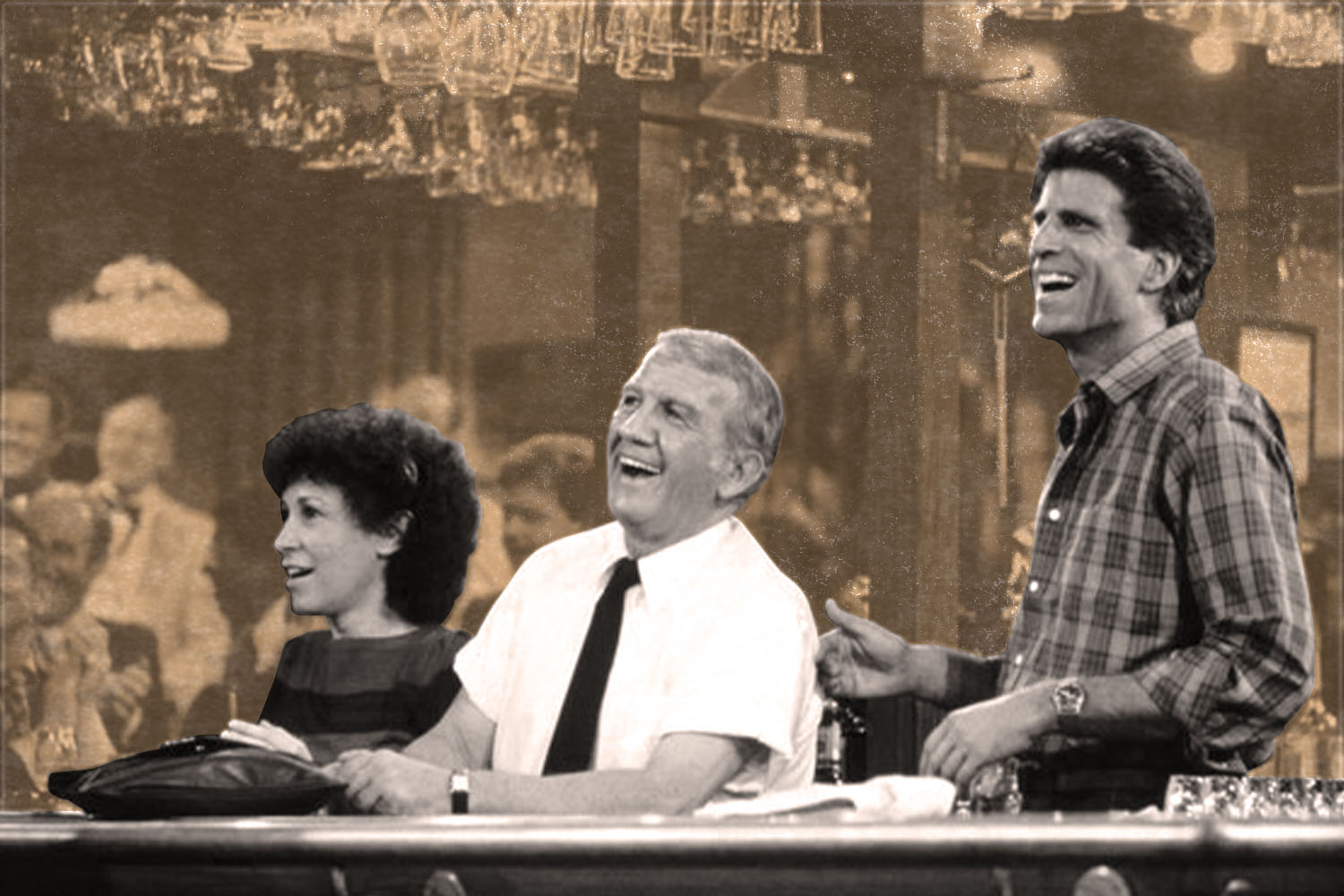

“Here we go,” the bar’s owner, Mike Stankovich, said as he showed me the news on his phone. Mike is one of those rockstar bartenders (literally, he once played guitar for the D.C. hardcore band Striking Distance) who pulls off an enviable cool that allows him to be simultaneously amiable and aloof. His personality is steady and reassuring, the kind of “let’s put things in perspective” guy you need when things start going south. Years ago, when he was working at the cocktail bar Alameda in Brooklyn, the New York Times described him as “one part Jello Biafra and one part Sam Malone.”

I didn’t say goodbye to Mike when I left that night because I didn’t know what goodbye meant anymore. Walking down 13th Street on my way home, a knot swelled up in my throat as I passed by the windows of the neighborhood’s bars and restaurants, watching employees through the windows as they wiped things down or stood, bleary-eyed, talking to a coworker or a customer, uttering some version of:

“I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

“I don’t know how I’m going to pay rent.”

“I don’t know about our health insurance.”

“I don’t know if I’ll be back.”

As the weeks pass, I find myself thinking about all of those folks, keeping tabs on a local Cincinnati bar and restaurant forum to see how they’re doing, sharing stories on Facebook and Twitter about their carry-out options just to make sure everyone knows they’re not gone. Not yet. At the same time, I go looking for replacements to fill the void. Ready-made worlds to make up for the one we’ve all lost. I find myself in the tiny farmlands of Yoknapatawpha County via Faulkner. I find solace in northeastern Tennessee via the Carter Family. I go to sleep listening to the lullaby tales of Lake Wobegon. But the place I escape to the most is a British-style pub in the heart of downtown Boston. The place I keep coming back to is Cheers.

Since the show premiered in 1982, when I was 12 years old, Cheers has always been a part of my life. Long before the Big Bad coronavirus reached our shores, I would watch old episodes on Netflix, mindlessly skipping around to the episodes I loved most while growing up — the one where Norm announces he’s left leaving Boston to start a new life in Bora Bora, but chickens out and hides in Sam’s office to save face. I usually don’t care which one I’m watching. Like any bar, some nights at Cheers are better than others.

But given the times we’re living in, I don’t watch “Cheers” mindlessly anymore. I watch it the same way I watch It’s a Wonderful Life each Christmas. I watch it for affirmation that life is still worth living, that a world of warm and convivial pubs once existed, and that one day they will exist again. Cheers is the platonic ideal of every bar I, and so many of us, have ever loved. “It just has that reddish glow,” the show’s executive producer Rob Long tells me over the telephone. “It looks the way a bar is supposed to look — it looks like home.”

Seems I’m not alone in my seeking refuge at the Boston bar, either. During the past few weeks, I’ve seen people posting about the comforts of rewatching it. “It is like a warm comfort blanket that celebrates people, community and friendship,” one person wrote. “Binge-watching Cheers, I’ve never wanted so much to go to a bar, whether they know my name or not,” wrote another.

Last week, the writer John T. Edge, director of the Southern Foodways Alliance, tweeted how he and his wife, Blair Hobbs, had just hit play on Cheers, beginning with the first episode. “Already laughing,” he tweeted, “may soon cry.” When I reached out to him about why he thought so many of us were turning back to the show, he wrote that it was Hobbs’s idea to rewatch it. “When I was paying no attention, she pressed play,” he wrote. “Three hours passed. Cheers played across the screen like a boisterous and beautiful wake. Like a tribute to every bar we have now lost, and every bar we hope to regain.”

“We feel wistful when we hear the musical theme,” Hobbs tells me. “It’s maudlin but moving. And in the context of the pandemic, it’s breathtaking what we took for granted. It makes us wonder if we’ll ever be able to safely return to physical companionship. At present, we can’t go into our favorite bakeries and bars where everyone knows our name. We miss it.”

It looks the way a bar is supposed to look — it looks like home.

I miss it, too. In the weeks that have followed the closings of Ohio’s bars and restaurants, I’ve found myself driving around the city, looking for signs of their eventual resurrections. At Mio’s Pizzeria Pub, I check in with my old friend Kelli Gagen as she prepares pizzas to be delivered to Kroger employees down the street, news crews at the local NBC affiliate and hospital workers at the University of Cincinnati. She’s giving her employees a pep talk, raising a glass to them and assuring they’ll be back better than ever. And I pray that she’s right.

A week later, on St. Patrick’s Day, I stop by Arnold’s, the city’s oldest bar, to pick up an order of corned beef and cabbage from chef Kayla Robison. When I get there Kayla is in the back kitchen, preparing an enormous batch of spaghetti and meatballs she will donate to other cooks, bartenders and servers who’ve lost their jobs. The barroom is empty save for the owner, Chris Breeden, and another customer I’ve never met before. Standing six feet apart, I learn that she works at an office furniture company around the corner. That she is afraid they’ll shut down the bridges soon. That she grew up right across the street from the house where I live now. Five minutes of conversation and I have a new friend. This is what I miss the most. Not so much the drinks, though never have I needed them more, but the Cliffs and the Norms, the Dianes and the Carlas.

“The show was never really about drinking,” says Long. “The thing about being drunk is it’s not that funny.” That’s not to say the show’s writers didn’t have fun with inebriation sometimes. Long points to an episode where Sam arrives to open the bar, turns on the lights, and sees Norm still sitting at the end of the bar, having never left the night before.

In one of my favorite episodes, Carla takes over as bartender and mixes a batch of her grandfather’s everything-but-the-kitchen-sink cocktail called I Know That My Redeemer Liveth, despite Sam’s warnings. When Sam greets a hung-over Frasier at the bar the next morning, the latter replies, “I’m sorry Sam. Your friend Frasier is dead. What you are looking at is his undead corpse. Alright, let’s review last night. I got knee-walking drunk, and now I am back in this bar a mere seven-and-a-half hours later, hungover. Well, it’s official. I have a problem.”

And yet none of the characters, aside from Sam, who was a recovering alcoholic, have a problem with drinking. Like most of us — especially now, as we feel lonelier than we ever have — they had a problem with the realities of life in general, says Long. “We just assumed the heart of the show was they weren’t really there to get a drink. They were there to be with each other. They couldn’t really face that fact, because they couldn’t face that they were so lonely — they couldn’t face the fact that these people, who could be so irritating, were their family and their life-support systems. But, sure, they can pretend they just came in for the beer.”

One thing I’ve realized while watching Cheers is how tired I am of the tricks and gimmicks of most modern TV shows. I don’t care about superheroes or science fiction; I don’t care about true-crime or men who own tigers; all I want is something human, something that can wear its heart on its sleeve, with enough restraint to keep things from getting saccharine. I want a story to unfold. I want the characters in that story to feel real, whether they’re elitist intellectuals or know-it-all postmen. Indeed, Long says a lot of us are probably nostalgic for the multi-camera-format show we grew up with. “Shows like Cheers were done like plays, he says. “Nobody is moving the camera around. You can’t do a quick cutaway or a flashback.”

Last night while checking social media, I saw a local news story about how Kelli Gagen is still feeding hospital workers and grocery store employees for free at Mio’s (this, while keeping her employees’ health insurance intact). I read that Kayla Robison and Chris Breeden were planning on a curbside fish-fry this Friday at Arnold’s this week, keeping the city’s Lenten traditions alive. And then I found a post on Longfellow’s Facebook page that just about broke my heart. “Although the space may lie dormant, it’s [sic] soul is still kicking. We will not let this pandemic seep into the culture we’ve all been crafting together for three years. We will survive this. Our community will be stronger…Look out for one another, you’re going to need friends when the dust settles.”

“When this is over — and it’s going to be over — people will come back from it with a new understanding of the things they love, but don’t ever think about,” Long says. “It might be the barber down the street, or the fried olives at Via Carota in the West Village — the little things that we have so many of in America today — the places where we eat, and the places where we drink.”

Last night, I turned on another episode of Cheers. It was the pilot — the one I haven’t seen in years. I watched as Diane Chambers walked into that beautiful, fake-Tiffany-lit pub for the first time; I laughed as the bon mots were tossed back and forth between her and her eventual suitor Sam Malone. I watched Diane’s heart break when her fiancé left her stranded alone at the bar, and the graciousness Sam displayed by offering her a job. He’s looking out for her, I thought. Despite his Lothario ways, he’s being a friend. He’s providing a second home. He’s being a true Sam Malone: The kind of barkeep we could all use right now. The kind of barkeep we love. The kind of barkeep who will be there, waiting for us, once all of this is all over. From the time he or she turns on the lights, until the final last call.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.