At a birthday party a couple of months back, well before the COVID-19 Era was upon us, there was talk about the SNOO. I already knew what it was, and what it purported to do, but my skepticism had won out. The idea that a parent would pay more than a thousand dollars for a high-tech bassinet, and the baby would actually sleep, seemed far-fetched. What a scam! What snake oil! It was, I presumed, a branch for which a desperate parent might lunge during the river rapids of a baby’s infancy. I was cynical about its efficacy in a way that only an obstructive sleep apnea sufferer can be about simple solutions.

Joni, a party guest, had a baby not long ago. A Manhattan doctor, she heard about the SNOO from a Facebook group, and bought one used last February before her daughter was born, for $600 — about half the cost of a brand-new model. (SNOOs on the secondary markets tend to run about that much, or slightly higher.) It was immediately effective; the baby routinely slept eight or nine hours during the first four months, and then 10 to 11 hours a night during subsequent months. When she’d wake up, Joni would watch as the SNOO’s white noise and gentle rocking eased her daughter back to sleep.

While she doesn’t know if the baby would have slept as well in a more traditional contraption, Joni gives the bassinet a fair amount of credit. Recently, in fact, she met Dr. Harvey Karp, the SNOO’s inventor, at a medical conference, and thanked him.

Karp’s story, which has been told in the New York Times, Vox and on morning shows, is now familiar: Starting in the early 1980s, he was a practicing physician in Los Angeles. For two decades, Karp taught pediatrics at the UCLA School of Medicine. His breakthrough, for which he was reportedly paid seven figures, was The Happiest Baby on the Block: The New Way to Calm Crying and Help Your Baby Sleep Longer, a 2002 book that mainstreamed his theory of the “the 5 S’s” to calm infants: shush, swaddle, swing, suck and side or stomach. The book was a bestseller, and was followed by The Happiest Toddler on the Block and The Happiest Baby Guide to Great Sleep: Simple Solutions for Kids from Birth to 5 Years.

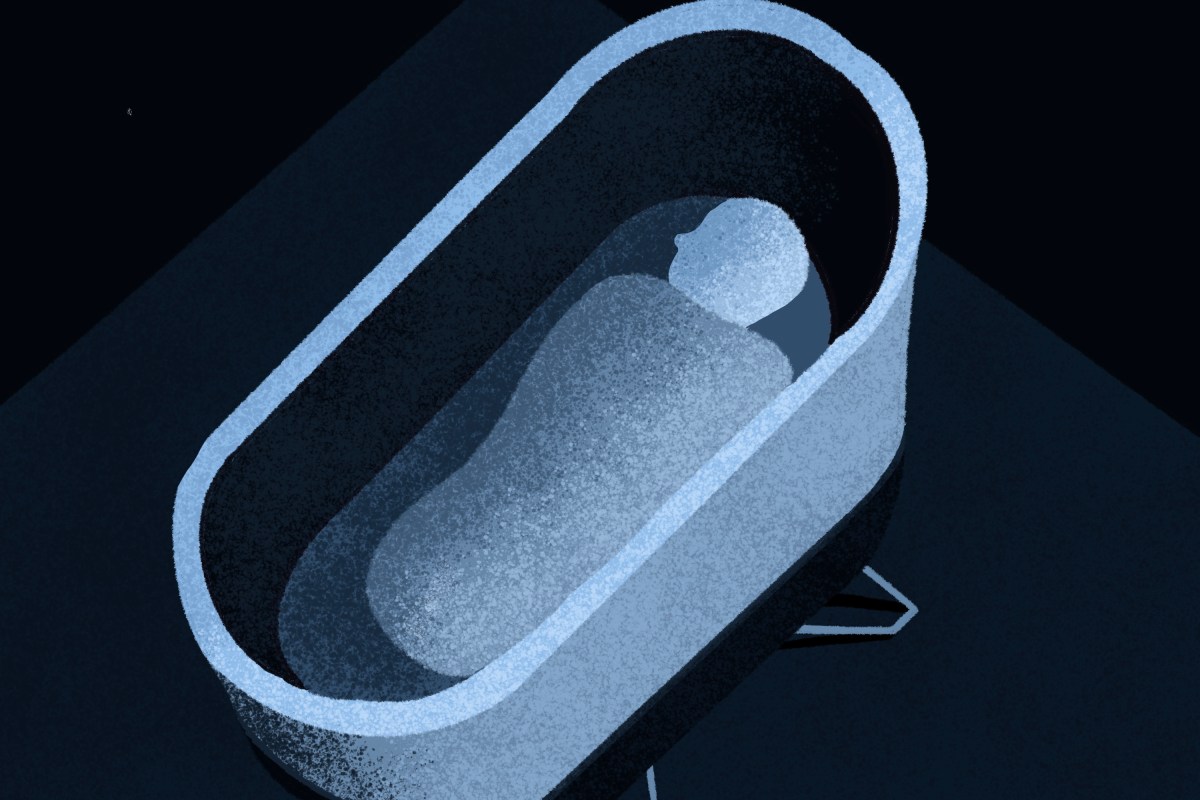

The SNOO was Karp’s next project. The smart bassinet — cleanly designed, white and brown on four skinny legs — debuted in 2016 for $1,300 (the price at which it still retails). Using a combination of rocking and white noise along with sensors that respond to the cries of the infant, the SNOO promised to lull a baby to sleep during the first months of life.

Karp’s innovation was based on a decidedly counterintuitive premise: babies want more noise, so let’s give it to them. Decades before, research had shown that a fetus experienced surprisingly loud sound in the womb, with decibel levels registering somewhere between 75 and 92. (As Karp will tell you, 90 is akin to a hairdryer.)

The SNOO simulated this experience. This was, Karp believed, a necessary measure. Babies, he famously theorized, are born too early; the first three months of life, during which colic is most common, are what he terms a “fourth trimester.” As he told a newspaper in 2002, “For the first three months, they’re really like fetuses. They’re more like they were inside the womb, but they’re born because they have big brains and they need to come out.”

The early months are also when babies are most susceptible to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), the risk to which is alleviated by the infant sleeping on its back. It followed, then, that during those crucial first months, the baby should be soothed and secure, but not disrupted. Karp’s idea was that a swaddled baby surrounded by amplified white noise — simulating the conditions of the womb — would be calmed.

According to the majority of accounts, the SNOO works. Chloe Schama, an editor at Vogue, has a typical story. She had just had her third child, and was already familiar with Karp, thanks to his videos on infant-soothing. And so, combined with desperation and deprivation, Schama was already open to that idea that the SNOO could be effective. It was. As she wrote in a 2018 essay about the experience, “at the first sign of witching-hour ghoulishness, we plopped him in the SNOO, stroked his cheek and walked away as it lulled him into his first bout of nighttime slumber.” Schama told me she’s since lent the bassinet to two pairs of first-time parents.

When I met with Karp in January, it seemed he’d accomplished more or less what he’d set out to do. In early 2019, Karp’s company, Happiest Baby, reported that 20,000 bassinets had been sold. That number has risen to more than 60,000 in the United States alone. Last year, Happiest Baby began a SNOO rental operation, which gave parents the option to pay $118 a month for a good night’s sleep. The rentals are now 50 percent of the units shipped. Most important: over the course of 72 million hours, there were no reported cases of SIDS in the SNOO.

Where, I wondered, does Karp go from here? If the hoped-for endgame is for every infant in America to get a good night’s sleep, what are the next steps?

At heart, this is a healthcare story about what our federal system does and doesn’t value. Until a decade ago, even something as basic as a breast pump — an essential for women returning to work from maternity leave — wasn’t covered. This changed with the Affordable Care Act, which led to a significant increase in the rate of breastfeeding as the largest insurers, including Aetna, UnitedHealthcare and Anthem, covered pumps. (An increase, incidentally, that may be reversed, as the Trump White House and Congressional Republicans weaken the ACA.) But that coverage was anomalous. Very little else — such as cribs, nursing bras or car seats — was covered.

So: What can Harvey Karp do to convince such companies the SNOO is worthy of coverage?

“You have to prove efficacy and cost efficiency,” he says.

Karp, an animated, bearded man in his late 60s, gesticulates as he talks. We’re sitting in a conference room in an unassuming office on the edge of Manhattan’s Chinatown. He’s wearing blue glasses and a parka with the logo for Greycroft, a private equity partner that led Happiest Baby’s $23 million Series B financing round in 2018.

What Happiest Baby needs, continues Karp, is research to convince insurers it’s in their interest to cover the SNOO.

Nearly a year ago, researchers in Amsterdam published results of a study using Karp’s bassinet, comparing the responses of infants to “mechanical soothing” versus parental soothing. “The results on the differences in the strength of the CR [calming response] between parental and mechanical soothing were equivocal,” wrote the authors. The heart-rate variability of infants was stronger when the parent was involved. However, they found, infants did exhibit a stronger calming response “in terms of [heart rate] when soothed by the crib than by the parent.”

Ultimately, concluded the researchers, “it remains unclear whether parental or mechanical soothing is more effective for calming infants.”

This is promising, but according to Karp, Happiest Baby needs four or five further favorable studies, hopefully completed in the next two years (that the SNOO was recently accepted by the FDA’s Breakthrough Device Program could help). “That’s kind of the critical mass,” he says, necessary to convince insurers that covering the SNOO will cost less than current expenditures for postpartum exhaustion. (Karp frequently cites obesity, car accidents and marital stress as consequences of the condition.) “All of that is being triggered by crying babies and exhausted parents. That’s the burden. If I can show you that we can significantly reduce those outcomes for a couple of bucks a day, you’re going to save a ton of money.”

That seemed, to me, like a sunny view of insurance companies. I didn’t think an insurer would want to cover such a product, I said. I couldn’t envision, say, Aetna paying for a $1,000 bassinet.

“They want to save money,” Karp says, “but they have to be able to defend their position.” (Calls to UnitedHealthcare and Anthem weren’t returned. Aetna declined to comment.)

“Each organization will have its own process for how it determines its clinical policies,” says Kristine Grow of America’s Health Insurance Plans. “Those policies are determined by a committee — typically led by a chief medical officer — looking at the basis of evidence of what care and treatments are found to be effective for better outcomes, better healthcare.” She adds, though, that the degree to which covering a product might increase premiums would be taken into consideration.

Over the course of seventy-two million hours, there were no reported cases of SIDS in the SNOO.

Change can be effected through other means, of course. Karp, reported the New York Times, grew up in a family that was “Democratic but not political.” I told him that, in an effort to get a sense of his politics, I’d checked his political donations: a smattering of contributions to presidential candidates Steve Bullock and Kirsten Gillibrand, as well as the DCCC.

Pretty liberal, but he didn’t seem to be a fire-breathing lefty.

“The good news is interest in infant health and new parents is not a partisan issue,” he points out. I told him I was incredulous, given the Republican Party’s historic indifference to ensuring Americans are covered. (Only weeks after we talked, in fact, the White House unveiled a budget that took aim at the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Now, amid the pandemic, Republicans are still trying to weaken the Affordable Care Act.)

Karp, in turn, pointed to bipartisan legislation from 2016 which provided grants to treat postpartum depression. He visits the Senate a few times a year, lobbying for different bills and meeting with staffers from the “Senate Moms” group.

“One of the issues that’s in hot debate right now is about paid family leave,” Karp says. “The argument is being made that that’s something that is good for the economy — that if you help women have some time off, they’ll raise their children better, that’s better for the child’s emotional health, et cetera, et cetera. It pays dividends and in the long range, it’s a good investment for our country.” (This is true; the potential economic impact of increased paid leave policies is mind-bogglingly large.)

For the time being, however, substantive paid leave is in the hands of corporations, more than 50 of which have partnered with Happiest Baby. Karp reels off the names of companies offering the SNOO as an inducement: Hulu. Snapchat. Qualcomm. Under Armour. Weight Watchers. YouTube.

“I was unsure if it would work,” says Rachel Racusen, director of communications at Snap Inc., the publicly traded creator of Snapchat and Bitmoji. She went on maternity leave in December 2018. Snap had begun offering a rental SNOO as a perk earlier in the year, as part of its 18-week maternity package.

Racusen’s daughter began sleeping in two- to three-hour chunks “pretty immediately,” she says. By the end of the four months, she was up to five-hour stretches, and getting up once a night to feed. These stretches allowed Racusen herself to sleep, and she credits the SNOO. “I would’ve been in pretty bad shape without it.”

At heart, this is a healthcare story about what our federal system does and doesn’t value.

Karp and I talked for a few hours. Toward the end, I asked what his ideal healthcare system would look like. And how could this be achieved? I would think about this conversation, months later, when I watched the American medical system be obliterated by a pandemic.

Karp’s politics, insofar as I could discern them, suggested he’d favor tinkering around the edges of the existing system. His passion, however, suggested a man willing to blow it up and start over.

”There’s so many middlemen in the medical system, that they’re siphoning off dollars that otherwise should go towards care,” he tells me. “We have to reduce the amount of money that’s being siphoned off for profitability, whether it’s pharma companies or insurers. I don’t have a set way that that should be.”

Karp said he wasn’t wedded to abolishing insurance companies or forcing them to be more competitive. “But I do know that that money is going out that really needs to go to healthcare.” More money, he continued, must be spent on doulas, midwives, nurse practitioners, physician’s assistants, rather than the current system, which pushes patients towards specialists.”

It sounds, I tell him, like he’s advocating for a systemic overhaul.

“Oh, yeah,” he replies. “There has to be. So we’ve had many systemic overhauls through the past, right? Medicare, Medi-Cal, Medicaid. We’ve seen a switch from self-payer to PPOs to HMOs, so this is the normal evolution. There are market forces, and those market forces can be nudged and encouraged by the government.”

It was nearly time to part ways. I was impressed with Karp, by the single-mindedness with which he has made sleep his mission. But I couldn’t stop thinking about the obstacles.

“You need a government that wants to encourage the market forces,” I say before we wrap things up.

“Of course,” he tells me. “That’s the precondition.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.