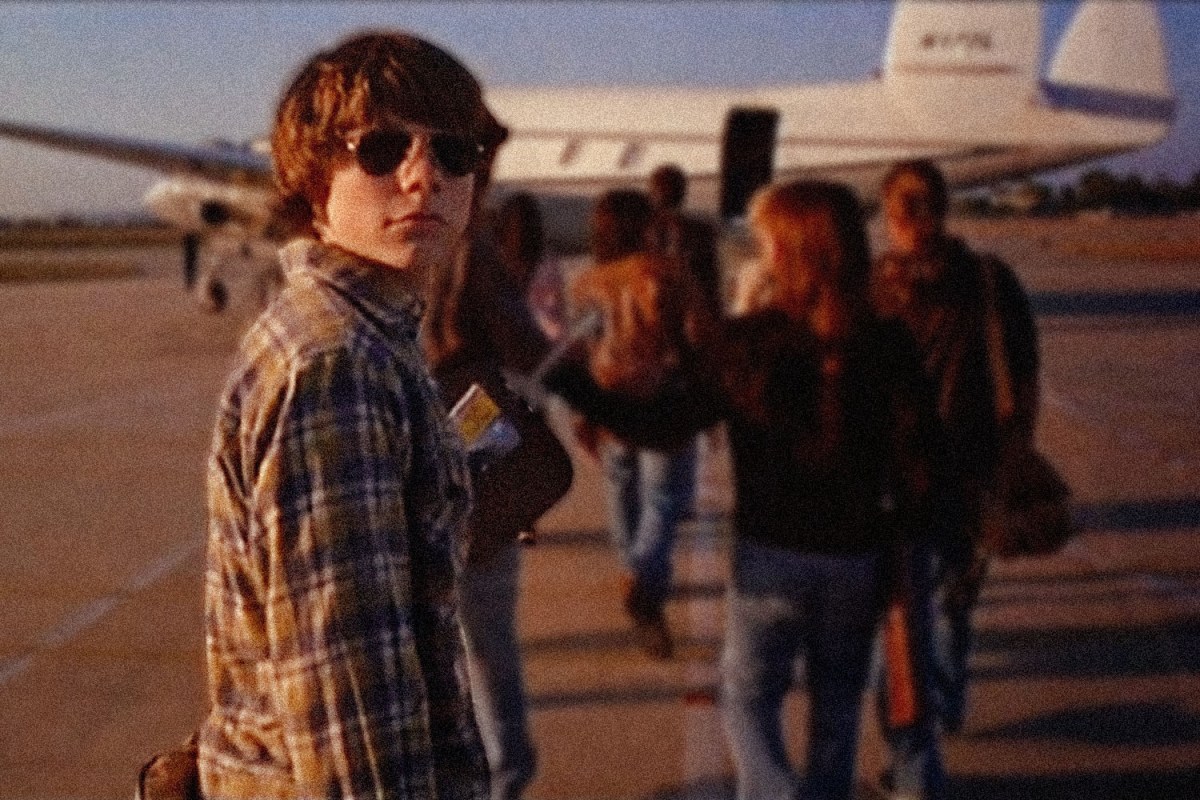

I can’t tell you the first time I ever saw Almost Famous, but I can tell you in humiliating detail all the ways it shaped my adolescence: How I wore a messenger bag instead of a backpack to high school every day because its protagonist William Miller did. How for many years I listened to “Misty Mountain Hop” every time I got in a plane because it reminded me of that sense of possibility and adventure in the scene it appears in as William and Stillwater roll over the Queensboro Bridge before the young journalist finds out his story’s going to be on the cover of Rolling Stone. How my AIM away message was a quote from Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s Lester Bangs: “The only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone else when you’re uncool.”

And because I am uncool, I can tell you all the mushy stuff too, like how rewatching it in a “Journalism in the Movies” class my freshman year of college convinced me to go into music journalism, how years later I’d watch it and maybe cry a little to celebrate nabbing my own Rolling Stone byline, how to this day I’ll put it on the night before a big interview to psych myself up. When the plane I was on en route to L.A. for one of the biggest stories of my career had to make an emergency landing a few years ago, I tried to keep myself calm by thinking about how I had somehow found myself in Almost Famous‘s plane scene. (I hadn’t, really: We had to land because of smoke in the cockpit, not a storm, and instead of a series of frightened confessions from people, the plane was eerily silent. But if I was gonna die, at least I could go out laughing to myself about the vague connection to my favorite movie.)

But I am far from the only one who saw director Cameron Crowe’s semi-autobiographical movie, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this week, and felt inspired. There’s an entire generation of music journalists who felt compelled to enter the field after watching the film.

“It’s funny because I was a big music fan, but I had never really considered being a music journalist before I saw Almost Famous,” says Billboard‘s senior director of music Jason Lipshutz, who has a vivid memory of recording the entire movie off of HBO onto a VHS tape to facilitate repeat viewings. “I was 14 and no idea what I wanted to do, but I remember the impression of someone who was a writer following this band around and getting a sense of their lifestyle. And the rockstar lifestyle never appealed to me ever — not only being a rockstar, but just the partying and all that. But the William Miller lifestyle, kind of observing and noting and documenting, was very interesting to me. It wasn’t until a few years later that I decided definitively that I wanted to be a music journalist, but [the film] certainly planted the idea in my head.”

Hilary Saunders, the managing editor of No Depression magazine, also found William’s innocence to be relatable after watching the movie as a teen. She saw it shortly after her own first major interview, interviewing the Goo Goo Dolls for her local newspaper at age 15, and watching William onscreen was an affirmation. “It was empowering in a way to see that and to know at that young age, ‘This is exactly what I want to do, and I can actually make a career out of it,’” she says.

Rachel Brodsky, a writer and editor who has worked for several music publications, including SPIN, found William’s earnestness to be relatable when she first saw the movie as a 13-year-old, and she says it inspired her to start consuming more music journalism as well.

“I definitely think I saw myself in William’s character a lot,” she says. “He’s not that much older than me in the movie. He’s got the wide eyes, sort of bushy-tailed thing going, which I identified with because I was honestly very innocent. Like I didn’t really do anything that badass growing up even well into my teen years. I was a very good kid, didn’t drink or do drugs. Then later, I think I got it on DVD, and that was one of the movies that I rewatched and rewatched. Not even a month would go by that I wouldn’t put it back on, especially as I got older and did start music writing for my high school newspaper and kind of put two and two together that this was something I wanted to do. I don’t think I was even a Rolling Stone reader that much at 12 or 13 yet, but I’m pretty sure that Almost Famous kind of started me off on reading Rolling Stone and starting to understand who Lester Bangs is, and what all the names they’re dropping in the film mean, and who Cameron Crowe really is.”

There’s a scene early in the movie where Lester Bangs warns William that he’s not entering the field at an ideal time. “Your writing is damn good. It’s just a shame you missed out on rock ‘n’ roll; it’s over,” he tells him. “I mean, you got here just in time for the death rattle. Last gasp. Last grope.”

“At least I’m here for that,” William responds.

And while journalists like Lipshutz, Saunders and Brodsky grew up watching that, they’d later start their careers just in time for what some might call another “death rattle” as music journalism — which straddles two struggling industries, music and media — looks completely different than it did in Almost Famous‘s era.

In the movie, William is initially offered $1,000 for a 3,000-word story on Stillwater. That’s in 1973, yet that’s still about as much as — or in many cases, depending on a number of factors like what publication it’s for, whether it’s for print or online, etc., significantly more than — what a music journalist would earn for such a piece today. Besides having to deal with low rates, constant layoffs and publications shuttering, the kind of access to artists that William gets is no longer commonplace.

“I guess in some way I knew that writers could have gone on the road with musicians for long periods of time at some point in the past, but I’m not sure I expected that was going to be my journey as a music writer,” Brodsky says. “Probably because when I graduated in 2008, the first messaging that I got was ‘there are no jobs, jobs don’t exist.’”

“I never knew a time, even in my earliest young adult years, where to do what William Miller did or what Cameron Crowe did would be possible,” she adds. “Anyone I knew who was a music writer, they were all just doing it for scraps. It looked sort of similar to today only, except for the fact that you could get away with paying people nothing a lot more commonly like 10, 12 years ago. Now you really can’t get away with doing that, but I just kind of guessed that like, ‘Well, I’m going to scrap and try and email everyone who could possibly let me do this.’ But I was never expecting to just get on a plane or get on tour bus. The best I could hope for at the time was to go backstage to interview somebody or have, like, half an hour with them.”

Like Brodsky, Lipshutz went into music journalism with his eyes open to the industry’s challenges, but while he says the movie is “a pretty dramatized version” of what it’s like, it did leave him with a sense of how the line between being a fan and being an objective observer can sometimes be a difficult one to walk.

“I think I knew that, unless you were doing a big story or profile or a cover story, you’re not going to get to follow a band around on the road,” he says. “Even now with cover stories, that’s still really not the case. The expectation I did have and what has always rung true the most to me about Almost Famous is the kind of push-and-pull relationship between journalists and artists where they’re from two different worlds and they’re both sort of interested in each other and sort of interested in what the other has to say, but also a little dispensive when it comes to getting their job done, where in Almost Famous you have this band that takes a liking to this kid. But then there are also moments where they call him the enemy and then William had to be drawn to this band, but also he comes to be pretty disgusted by some of their behavior. You want to develop a relationship, but you also have to have that kind of wall up of ‘these are not your friends, these are your subjects,’ or ‘this is not your friend, that journalist is documenting your moves objectively.’ That part always rang the most true to me.”

But despite the fact that it depicts a bygone era, Almost Famous has endured and become a cultural touchstone — not just for music journalists, but for anyone who feels it in their bones when Sapphire describes what it means to be a fan, “to truly love some silly little piece of music or some band so much that it hurts.”

“I think there’s so much heart in that movie,” Saunders says. “It really captures sort of human relationships in all of their varied and nuanced forms. And I know that this is very idealistic, but I think that Cameron Crowe just did such an incredible job of showing how much music really means to people and how much it affects our day-to-day lives. And not just in the iconic scene of singing ‘Tiny Dancer’ on the bus, but from various stage shots of those big, pyrotechnics-filled scenes to the more subtle choices of other song selections playing in the background that are quite literally reflective of the soundtracks to our lives. I think it’s just a very human film.”

“I think it’s two things,” Lipshutz adds. “I think, first of all, the movie’s good. That’s the most important thing — it definitely holds up, you gravitate toward the characters, and all the actors in it are so excellent. Sentimentality sort of works in movies, so I think that’s the number-one thing. I think the second thing is it’s the definitive kind of music journalist movie, where I would struggle to name another movie that’s so focused on a music journalist experience.”

Of course, the experience portrayed is a very white, male one, and while the film does attempt to address the ways that female fans like Penny Lane — who, it’s important to remember, is supposed to be just 16 years old — were exploited back then, the stereotypes and the fraught gender dynamics remain to this day. (In a disgusting case of life imitating art, musician Mark Kozelek, who has a scene in the movie on the tour bus where he implores his bandmates to “look at all these fucking tasty-looking high school girls” out the window, was recently accused of raping a teenager.)

Female music journalists still have to fight the misconception that they just want to sleep with the bands they’re covering. In 2010, when a female journalism student on College Jeopardy mentioned she was inspired by Almost Famous, Alex Trebek couldn’t wrap his mind around it. “You want to be a groupie, in other words,” Trebek told her. When she said no, he persisted, saying, “But it would be kind of fun.” “Not the groupie part,” she responded, “but following a rock band and seeing what that lifestyle would be like I think would be very interesting.” Trebek looked into the camera and grinned: “She wants to be a groupie.”

That scenario is all too familiar for Marissa R. Moss, a journalist who has written for the likes of Rolling Stone, Billboard and NPR.

“I was in college in New York studying to be a journalist [when I saw the movie], and I simultaneously enjoyed it while also feeling very frustrated,” she says. “I already knew 90 percent of music journalists looked like grown-up versions of William Miller, just add or subtract a mustache or glasses. I already saw how folks treated me when I was out reporting in the field, and when I told people I wanted to have a job like in Almost Famous, most assumed I was talking about Penny Lane and not William Miller to the point where I started to make a running joke about being ‘William Miller with Penny Lane’s wardrobe’ to diffuse the situation to make other people more comfortable. I wish I had felt comfortable enough back them to say exactly what I wanted to say and not give a shit. As much as I loved the movie, it always reminded me that people like William Miller were going to have a ticket in and women were going to have to work past being seen as groupies, even if we were trying to do our job. I can’t even imagine how alienated from this world a non-white person must have felt watching that movie.”

And yet, despite all the unsavory aspects of the industry, Moss, Lipshutz, Saunders and Brodsky all press on. For Brodsky, the small moments of connection with artists — like the one at the end of Almost Famous when Russell’s eyes light up and he flips his chair around to dig into his love of music with William — make it worth it.

“I think there’s this misconception that what we do isn’t real work because we’re writing about stuff that we are fans of,” she says. “And I think the movie does a pretty good job of showing how the glamor has a serious gross underside, which you see when Penny Lane overdoses and when everyone’s exhausted and fighting with each other and in the hopes of getting famous, their plane almost crashes and they’re all kind of like sick of each other by the end of the tour. And yet it’s like, it’s all worth it just to see William Miller forge this connection with Russell and sit with him at the end and have this really deep conversation. And I think as journalists, we still have those moments. When we have five minutes of a meaningful connection with someone that we’re interviewing, that kind of makes it all worth it.”

“This is a hard industry, and music journalists are at the intersection of two industries going through massive upheaval right now,” Saunders adds. “And so it would be so much easier to make a living doing literally anything else. And this is what I tell folks asking for advice or anything, like if there’s anything else you think you could do, do it, because you’ll more than likely have an easier life and make more money. However, if you can’t think of doing anything else in this world than writing, telling stories, talking to people, listening to music, trying to share all of this with someone else, then for the love of god, keep writing. Because it takes that sort of passion and drive to keep going in this field. I don’t think that anyone who is still in music journalism does it for any other reason but that they love it so fucking much. And if you have that love, then keep doing it.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.