I’ve had a complicated relationship with wearing a suit. I grew up appreciating the style of writers like James Baldwin and Vladimir Nabokov, people who had a flair for wearing suits and did so flawlessly, with a personal touch. Baldwin could do the Ivy look with a slim navy suit, but he also never had problems with replacing the tie with an ascot. And while Nabokov wasn’t known first for his sartorial prowess, he always showed up in a suit. That was how things used to be, but not so much anymore

So when I tried my hand at finance through college internships despite having literary ambitions, my experience pretending to be a suit-wearer gave me suit PTSD. When I finally graduated and bounced around some jobs in which a tie and blazer weren’t required, I forgot about suits, or why anyone would wear one in the first place.

My current job is in the nonprofit sector, and involves taking government meetings in state capitals, primarily London and Brussels. As such, it became clear to me that I’d have to grow up and buy a suit.

But the more I thought about it, the more I didn’t just want any old off-the-rack suit. I wanted a suit like the ones Nabokov and Baldwin wore — something that would make me stand out from the thousands of other backpack-wearing political staffers who run around frantically with both thumbs pressed to their phones, always responding to one urgent missive or another.

A colleague of mine always looks quite dapper when we’re traveling. I confessed to him that I was looking to invest in a suit, something distinctive, something that would stand the test of time. He smiled, and told me that he would introduce me to his tailor. There was one catch: I’d have to go to London.

The Shop

When you get off London’s District & Circle Tube line at Monument station, walk north until you see the indoor-outdoor Leadenhall Market on your right, turn left down a series of narrow alleyways and wend around St. Michael’s church, you’ll find the bus-stop sized storefront of MacAngus & Wainwright.

The waiting room is on the ground floor, where you’re greeted and sat. Shelves stocked with swaths of fabric line the waiting room walls. The shop expands upwards instead of outwards — narrow, spindly staircases lead to three workrooms stacked on top of one another.

The store sits across from a bar called Jamaica Wine House, which used to be the oldest coffee shop in London, established in the early 1600s. The little shop and the cozy pub across the street make the experience of visiting a sort of Harry Potter scene for adults, as if you’ve unexpected stumbled on a magical hideaway just beyond the bustling streets of the City of London.

The Tailor

Dave Garrad is a small man with a considerable paunch and a mousy face who dresses impeccably, as he’s made all his clothes himself.

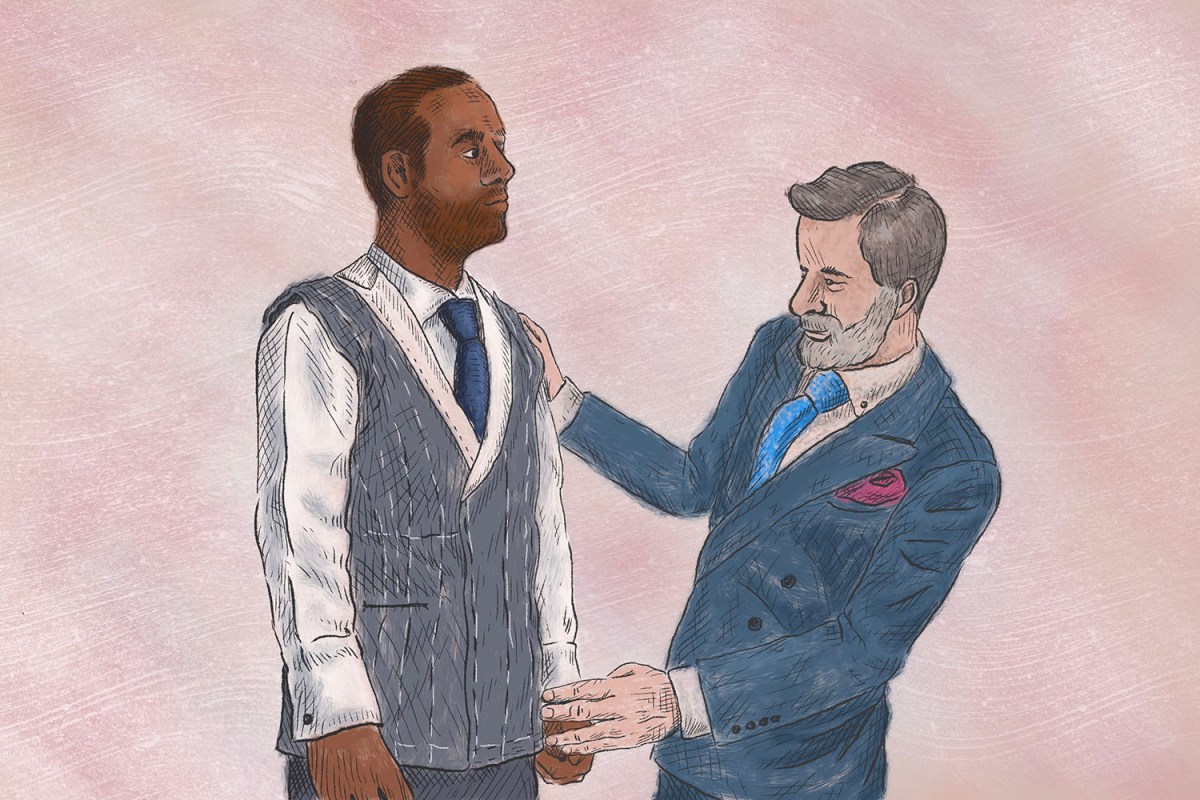

He greets me warmly when he emerges from his work room. We exchange pleasantries, and he asks me why I am visiting him, even though he almost certainly knows. I tell him I am interested in a suit. He beams.

Step One: My Measurements

Dave tells me that we’ll begin with the creation of my “paper pattern,” which he says he’ll show me during my “rough fitting.”

As he measures me from every angle twice to ensure he has the right dimensions, I ask him about his career, how he found his way to MacAngus and Wainwright. He tells me he got a job on Savile Row after tailoring school, and that the shop managers on “the Row” have strict rules about dress codes and specific entrances and exits for the tailors to take through the backs of the shops. Dave would stride through the front door every morning wearing a Hawaiian shirt and flip flops in the summer and a sweater and sweatpants in the winter, enraging the shopkeepers, but he was such a good tailor that they refused to fire him. He said he quit soon after he built a book of business and began working from home, and only began making his clothes at MacAngus and Wainwright when his wife said they needed more storage room in the house. He tells me he rents the workroom at the shop, and, in exchange, the owner of the shop takes a cut of the clothes he sells.

Step Two: The Fabric

Dave says that the next step of creating the suit is choosing the fabric, and asks me to tell him what I am looking for in the most abstract terms. I tell him about Baldwin and Nabokov, that I want something stately, something that I can wear in a work or a casual setting, and preferably something oriented toward winter, given people dress more casually during summer meetings.

Dave pulls books full of fabric swaths off the shelves. I touch and admire each one. Reds, greens, blues; solids, checks, squares. After a little while of searching and thinking, I tell Dave I wan something with a blue base, as blue is pretty standard in a work setting, but with a pattern, given I want something that will pop out. Dave believes that would work, but that I should try to keep the flair relatively neutral, and suggests a navy blue tweed with a light green check. There is something so distinctly British about the person helping you knowing what’s best for you even if you don’t. It might not immediately be what you want, but it doesn’t take long to realize the suggestion is the correct one.

Step Three: The Style

After I select the fabric, Dave asks if I am “thinking one-button, two-button or three,” but quickly reminds me that my fabric is quite thick, so a three-button style might be too hot. I ask him the stylistic difference between the one-button and the two-button, and he tells me the one-button is typically reserved for more casual or summer suits. I happily go with the one-button.

I tell him that I’d like the suit to fit my form fairly tightly, but he reminds me of the density of the fabric, and suggests some tricks if I want it to fit my form — longer vents in the back of the jacket, and only lining the pants halfway down, so there’s more room for my body to breathe. He assures me it will be form fitting enough but not uncomfortable.

Step Four: The Pockets

I tell David I want a breast pocket on each side and a pen pocket on the left, given I’m right-handed. He agrees and then asks if I’ve ever heard of a “poacher’s pocket.” I admit I haven’t, and he explains that a poacher’s pocket sits inside the jacket near the hip-line, and can be used for wallets and keys. Breast pockets can get too bulky for these items to fit comfortably, he explains, while putting wallets and keys in back pockets can make it uncomfortable to sit down and can make you vulnerable to pick-pockets. I agree. The poacher’s pocket is the way to go.

He then mentions that if I’m going with a poacher’s pocket I don’t need back pockets on the pants. I balk at that. What if I need to take my jacket off but don’t want to leave my wallet in it? He admits I have a point, and suggests a single back pocket on the right hand side for my wallet. I wonder for a moment if I made a bad choice. Dave is there to guide me. I think about that British way of politely telling you you’re wrong. It’s an art form. Did I make a mistake?

We move to the front pockets. He tells me the pants he and I are both currently wearing have “side pockets,” where the pocket is cut vertically, but he says he can also cut the pockets into the pants horizontally — a style called “cross-cut pockets” or “frog-mouth pockets.” He shows me a pair of pants with frog-mouth pockets, and they look so unique I can’t say no.

Step Five: The Extras

After we finish discussing the pockets, he starts to throw the kitchen sink at me. The full English, if you will.

Turn back cuffs on the sleeves of the suit? Yes.

Cuffs on the bottom of the pants? No.

What about a different color under the lapel? He starts pulling out swaths of fabrics. I point out purples, reds, and greens, but he advises me to pick something less flashy, as the very presence of a different color on the underside of the lapel will call attention to itself. I go with a light blue.

Then it’s time for the buttons. He points to a framed array of buttons on the wall, the title of which reads “2 Hole Real Horn Buttons.” Real horns? He tells me that my suit buttons will be made from the horns of a Scottish stag. When a stag’s horns fall off in the winter, farmers collect them and sell them to button-makers. When summer comes around, stags regrow their horns. He encourages me to pick a shade I like. I select a greyscale tortoiseshell.

Last but not least: the lining. Dave brings out more photo album-sized books, one filled with plain colors, one filled with paisley-patterned fabrics and one filled with fabrics bearing special designs. I pick up the design book and gloss over patterns depicting London, Paris, New York, Martini glasses, flamingos, tennis rackets. I finally settle on musical notes set against staff paper. It’s a gorgeous pattern, elegant and yet refined.

Dave asks me why I picked that lining, and I cited my love of jazz, specifically the music of Dexter Gordon and John Coltrane. Dave says he prefers soul music, and talks about how he raised his kids on a steady diet of Aretha Franklin. Five minutes later I find myself in a little tailor shop in the heart of London arguing about who had a better voice between Al Green and Marvin Gaye (Marvin, of course). We agree to disagree, shake hands, and he tells me he will let me know when my suit is ready for a rough fit.

Step Six: The Rough Fitting

Four weeks later I wake up to a text from Dave letting me know that the “rough cut” of the suit is ready for a fitting. I start planning my next trip to London.

When I finally make it over a few weeks later, I walk into the store and Dave takes me into his work room on the shop’s second floor, where he has me put on the “rough cut,” which is essentially broadly cut swaths of fabric comprising the various elements of my suit, all strung together with white pieces of twine. The legs of the pants barely stick together. Wearing both of them feels like a diaper; the arms of the jacket are like pool floaties I donned when I was a little kid. But Dave seems pleased. The cut works, he tells me.

He then mentions he’ll follow up on his promise, and leaves the room reappearing a few moments later with a cylindrical tube. He pulls out pieces of brown paper with size markings on them, which he tells me was my “paper pattern.” Each piece of paper is the size and shape of each piece of my suit — the left side of the torso, the right sleeve, etc. He says that he will keep my paper pattern, that whenever I want a suit, my measurements will be perfect. He slides the pieces of paper back into the scroll and leaves the room.

Step Seven: The Friendly Pint

When he returns, I ask Dave if he’s off for the day and he’d like to join me for a pint at the Jamaica Wine House. He agrees, but “only a half pint,” as he’s driving home to the country thereafter.

As we stand outside and chat, the street outside the pub fill with a sea of men in navy suits and women leaving their banking jobs to start drinking. Dave gazes at them forlornly, commenting on the way their suits don’t fit them, about how their belts and shoes don’t match colors, claiming they “take no pride” in their appearance.

I’ll admit there was something a bit refreshing about his sadness. Up until I walked into his shop, I was like all of them. I’d lacked pride in my formalwear; now, with Dave’s guidance, I am finally on the right path. My Bildungsroman into the world of fine British suits, if you will.

As we sit in the pub, Dave takes tiny sips from his pint to make it last as we chat about music, life, art and everything in between. We finish up, shake hands and Dave tells me we’ll meet again when it’s time to pick up the suit.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.