These stories are a little messier than the versions you read in your history textbooks. Take a look at the sordid, unsavory and insalubrious backgrounds of the greatest explorers the world has ever seen.

Ferdinand Magellan

The Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan is best known for his circumnavigation of the globe by sea, though he didn’t make it all the way — he was stabbed to death while attempting to convert natives in the Philippines to Christianity — and there are arguments over which of his remaining crew members were first to complete the expedition.

What’s not as well-known about Magellan are the lies he told about his expedition. He and his crew reported there were massive natives in what’s now known as Argentina, telling stories of “a naked man of giant stature” who was “so tall that we reached only to his waist.” They also reported seeing him “dancing, singing, and throwing dust on his head,” and went on to name an entire race — the Patagons — after these people. The name stuck. Have you ever been to Patagonia? That’s where the name comes from.

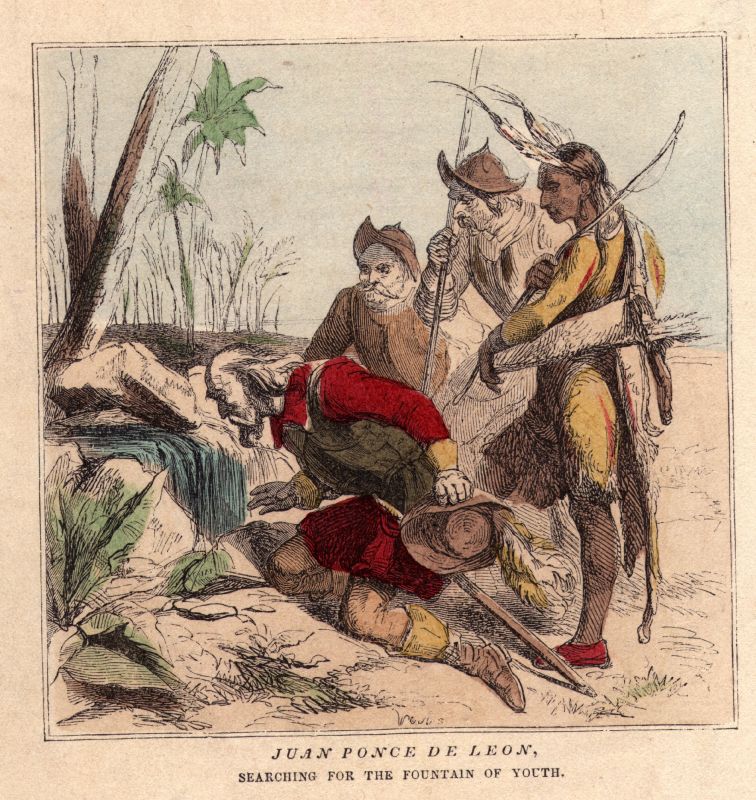

Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de Leòn is credited for discovering Florida and is known for supposedly finding the Fountain of Youth in St. Augustine. But a historian in the New York Times argues he found neither — he didn’t even get close to the city, T.D. Allman says, and the state was likely seen by Portuguese navigators nearly fifteen years before Ponce de León set foot on land there. He was struck by an arrow and “died of fever in Havana, having discovered nothing, founded nothing and achieved nothing.”

He did, however, fire the first shots in “what would turn into a 300-year war of ethnic cleansing. More American soldiers would die trying to subdue Florida than in all the Indian battles in the West.”

He still has Puerto Rico, we guess.

Marco Polo

The way it’s told in his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, this 13th-century Venetian merchant was an unparalleled wayfarer who encountered mythical creatures and fought in dangerous battles during his time in Asia. Actually, the creatures were just animals he hadn’t encountered before, like crocodiles, which he described as sharp-clawed “serpents” that could “swallow a man…at once time.” He also thought that, because of their horn, Asian rhinoceros were unicorns.

In reality, his contemporaries and many historians today think his tales were a little too tall — there are battles he said he was in, for example, that took place years before he arrived. It also wasn’t smooth traveling. His family barely made it out of Asia alive, and they lost a ton of their money on the way home after being robbed. He was only home for three years when he ended up in prison for leading a galley against a rival Italian city-state.

It was there he met Rustichello of Pisa, who became his ghostwriter. Together, the two of them wrote the book together between 1298 and 1299 when they were freed.

Christopher Columbus

The most controversial explorer on this list, Christopher Columbus is known for sailing across the Atlantic in 1492 and discovering North America and parts of the Caribbean. Depicted for centuries as a hero, American students are taught in school that Columbus brought together Native Americans — called “Indians” by Columbus, as that’s where he thought he’d landed — and pilgrims to eat a delicious feast, which we celebrate as Thanksgiving today.

The reality, of course, is much more sinister.

“In an era in which the international slave trade was starting to grow, Columbus and his men enslaved many native inhabitants of the West Indies and subjected them to extreme violence and brutality,” History.com writes. During his time as the governor there, Columbus reportedly enforced “iron discipline.”

“In response to native unrest and revolt, Columbus ordered a brutal crackdown in which many natives were killed; in an attempt to deter further rebellion, Columbus ordered their dismembered bodies to be paraded through the streets.”

He and his crews also introduced an onslaught of diseases that the immune systems of Native Americans weren’t prepared for, which some have equated to biological warfare. Genocide expert David Standard estimates that, beginning with Columbus in 1492, Europeans killed between 70 million and 100 million indigenous people over an 80-year period.

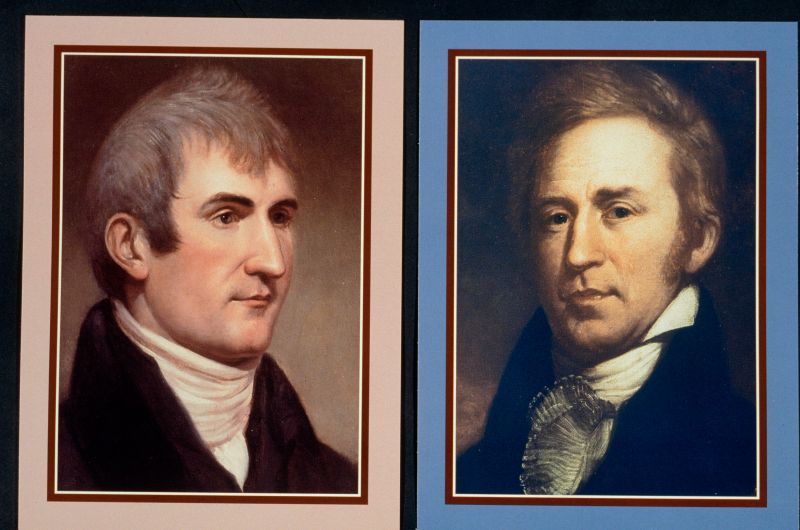

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

Though they’re remembered as two of the bravest explorers of the New World and were the first to solidify the brave and adventurous spirit long-associated with the American West, things are a little more complicated than that.

For one, the expedition wasn’t just the two of them. There was a whole Corps of Discovery that had more than 45 people in it, including Clark’s slave, York. In fact, History.com notes, later in the journey when the group was deciding where to camp for the winter of 1805, York and the Native American Sacagawea were allowed to give their opinion on where the group should hunker down. The website references the historian Stephen E. Ambrose when stating: “This simple show of hands may have marked the first time in American history a black man and a woman were given the vote.”

Later, when they returned from the expedition, Clark actually adopted Sacagawea’s son, Jean-Baptiste, and became the legal guardian of her daughter Lisette when Sacagawea died in 1812.

Things did not fare so well for Lewis. Though he was twice stopped from committing suicide, Lewis — who suffered from depression and mood swings throughout his life — was found dead in 1809 with gunshot wounds to his head and chest. Historians think it likely that he killed himself.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.