A new pastime of our current pandemic era is scheduling out an ideal first week back. Vaccines are rolling out, which means an end is in sight (if not exactly on the calendar), so you better be ready when the shackles are off and the socializing-starved masses flood the streets. What’ll it be, a packed movie, Broadway musical, then cap it off at the Met Opera? Or how about a jazz show in the city, then a sweaty concert in Brooklyn, and then back across to the Apollo?

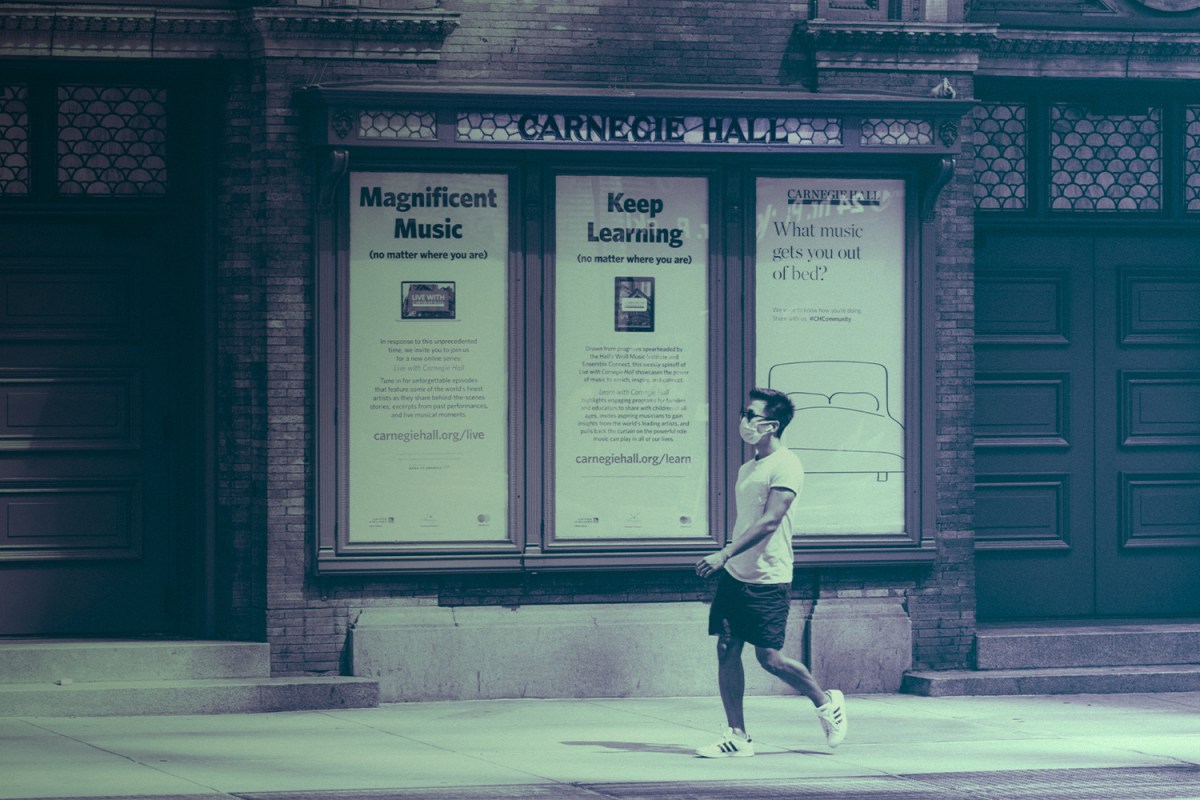

This is something Laura Aden Packer has given plenty of thought to. “I would be out every night and sitting in some theater — watching dance at The Joyce or going back to Carnegie Hall for a concert,” she recently told InsideHook. “Certainly people who work in the arts have never gone this long without sitting in a theater with other people and watching magnificent art in front of you, whether it’s dance or theater or music.”

Packer doesn’t work in the arts per se; as the executive director of the Howard Gilman Foundation, she’s continuing the work of a legendary arts patron. In other words, the kind of work she does is the reason the rest of us will be able to emerge from the COVID-19 crisis with an intact performing arts scene in New York City.

In a normal year, Packer oversees the distribution of about $20 million in grants to a variety of performing arts organizations across the five boroughs. During 2020, as the pandemic ravaged theaters, dance companies and orchestras, the foundation upped that number — to an astonishing $32 million. It’s what Gilman would have wanted. If his name sounds familiar, that’s because it graces Gallery 852 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a film auditorium at Lincoln Center and the monumental Howard Gilman Opera House at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and his namesake foundation can in happier times be found listed in the programs at any number of New York performances.

Individuals can only do so much to support the arts that they treasure, and as the pandemic drags on and opening dates keep getting pushed back it can often feel like a lost cause. But Packer and the foundation she leads are working overtime to save the people and places that make up the cultural center of the world, albeit quietly and without much fanfare. So we called up Packer to give her that much deserved fanfare, and see what it’s like putting these emerging and hallowed institutions — from the Metropolitan Opera to the New York City Ballet to The Shed — on her back.

InsideHook: How did you get into the business of arts patronage and philanthropy?

Laura Aden Packer: I spent half my career working in nonprofit theater. After doing that for 20 some years, I started working at the [Geraldine R.] Dodge Foundation in New Jersey. I was hired as their arts program director, and at the time the Dodge Foundation was the largest private funder of the arts in New Jersey.

I worked there for 13 years and then I was hired as the new executive director of the Howard Gilman Foundation, in 2014, when this foundation had been dormant for about 12 years or so after Howard Gilman had passed away. The board really wanted to reboot the foundation. So 20 years in philanthropy, 20 years in nonprofit theater. I’ve been on both sides. I had to raise the money and spend sleepless nights worrying about can I make payroll? And I’ve been on the other side trying to help nonprofit leaders sleep better.

Can you give us a sense of who Howard Gilman was and the institutions or artists that he cherished?

Howard Gilman was an incredibly generous philanthropist. He did a lot of funding of HIV/AIDS [research] in the ‘80s, he did a lot of funding for heart disease research, but he also had a great passion for endangered species. In terms of the arts, he was incredibly philanthropic; dance and theater were his two great passions. He was very, very close with [Mikhail] Baryshnikov. When Baryshnikov defected [from the Soviet Union] it was Howard who was his sponsor, and that started this lifelong close personal relationship, like a father-son relationship, that Howard had with Baryshnikov. He was born and raised in New York City and loved New York City and loved the arts community.

What’s it like at the foundation in a normal year? How do you choose which entities to support and how much money to give?

For us there’s been no normal year, though 2020 was certainly the most abnormal of all. In 2019 we made about $21 million, $20 million in grants in New York City. And then in 2020, our board — recognizing what was going on in New York and especially how the performing arts organizations that we funded were being decimated — increased the amount that we would be able to make in grants by $12 million. So in 2020, we actually made $32 million in grants.

There are different qualities that we look for in our grantees, but if you look at our roster, we’re pretty much funding almost any performing arts organization, any dance company, theater company or music ensemble — we’re funding a vast majority of them that have budgets larger than $250,000. Not all, but we have over 200 grantees.

We spend a lot of time with our grantees. Up until the last year, not only would they submit an application, but then we would go to where they work, do a site visit. We always see a performance or a rehearsal. We’re very hands-on in that way. And the other core value of ours is that we respect our grantees and that we acknowledge that they know way more than we do what they need money for. That’s basically our question: What do you need money for? What can we help you with?

This year, the board maintained that same level of funding for 2021, as we had last year, which is $32 million for grants, which is great because the crisis is not over — the crisis is continuing. In some ways, ‘21 is even worse than ‘20 for a lot of organizations that still won’t be open this year or have audiences returning to them this year.

Do you spend your free time also going to see the arts or do you limit it to your professional life?

I mean, I was seeing shows up until literally the night before New York shut down. I was at the theater the night before.

What was the last thing that you saw before everything shut down?

I saw Cambodian Rock Band at Signature Theatre and Six on Broadway. It was a Wednesday, so I had gone to a matinee and an evening [performance], because I knew — by then that was March 11 — everybody knew that things were shutting down. I saw several shows in a row: Friday, Saturday, Sunday I was at Carnegie Hall. But I would say that not just me, but my staff — the foundation has four program officers and they’re really the ones who primarily have the relationships with our grantees — they’re also all always out seeing performances as well.

Being a major force in New York City arts philanthropy, are there any places you feel have been under recognized in receiving funding?

Some people would certainly argue that historically — and I’m not just talking about Gilman because we’ve really only been around since 2014 in this iteration — but historically there has certainly been an underfunding of organizations that are led by people of color or serving communities of color. There’s all kinds of data historically about where philanthropic dollars go, and that certainly shows that those organizations have been underfunded for many, many decades. Some of the largest grants we make are to some of the most diverse arts organizations in the city like Ballet Hispánico or Dance Theatre of Harlem or National Black Theatre, so we have a roster of a lot of organizations of color. But everybody can always do better in making sure that voices are being heard and that communities are being served and that arts organizations in those communities are being supported.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, you have these large legacy organizations like the Metropolitan Opera that are also weathering unprecedented times. What worries you about what they’re going through?

To be honest, I think that the larger institutions in the city, most of them, not all of them, but most of them have endowments. They have well resourced board members. So in a way I’m certainly less worried about them than I am about mid-sized organizations. I think a lot of smaller organizations, organizations with budgets of $3 million and under, are able to be pretty nimble and have figured out ways to survive. I think it’s those middle organizations between $3 million and $10 million, $12 million, those are the organizations that we really focused on more than the big organizations.

Here is what we did this year in 2020, just to give you an idea, which is very different than what we’ve done before:

We normally have three grant cycles. People apply and then they get notified in March, July and November. Last year, we had our March board meeting in the first week, so all those grants were approved — and then the next week the city closed down. The first thing we did was we accelerated all of our payments, all of our general operating support grants to all of our grantees, whether they were in cycle two and normally would have gotten a check in July or in cycle three, where they normally would have gotten a check in November. We sent everybody a renewal of their general operating support without needing to apply or anything. They just sent us a paragraph about how they were being impacted by COVID.

Then in August, we did a whole ‘nother round of general operating support grants to all of our grantees. Again, they didn’t have to apply. In fact, they didn’t even know the money was coming, so it was a wonderful surprise for a lot of organizations.

Then in the fall, we turned our focus to our small and mid-size organizations. We made very specific project grants to them based on what they told us they needed. We were hearing from our grantees that they needed funds, for example, for technical equipment: cameras, mics, things that they needed so they could do streaming shows on the internet. They needed computers and laptops so their staff could work at home. They needed upgraded broadband so they could stream from their buildings, from their empty stages. They needed money for artist fees. We did grants for all those things.

It must be such a great feeling to be able to offer that to these people.

Very much. And none of us can do anything without our board. Nobody who runs a foundation can do anything without the board’s approval. So our board has been tremendous and they were tremendous from the very beginning, from that second week in March, when we told them everything that we wanted to do. We also made a million dollars in grants to organizations that were providing funds for individual artists and arts workers. That was very early on, in April, when people just needed money for groceries and medicine before they’d been able to get on unemployment.

The other thing we did in March of last year was we purchased Zoom licenses for all of our grantees. And then we renewed that for this year for 2021 — we renewed everybody’s Zoom licenses. So those are the kinds of things that we’re trying to do. We’re always constantly trying to help them get what they need in order to be able to produce fabulous work on stage.

It’s been torturous, but I’m sure that New York will come back. New York can’t come back without the arts.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.