“He realized that he had to have a quiet mind in order to do what he could do, but he didn’t know how to explain it. But he knew that’s what he had to do.”

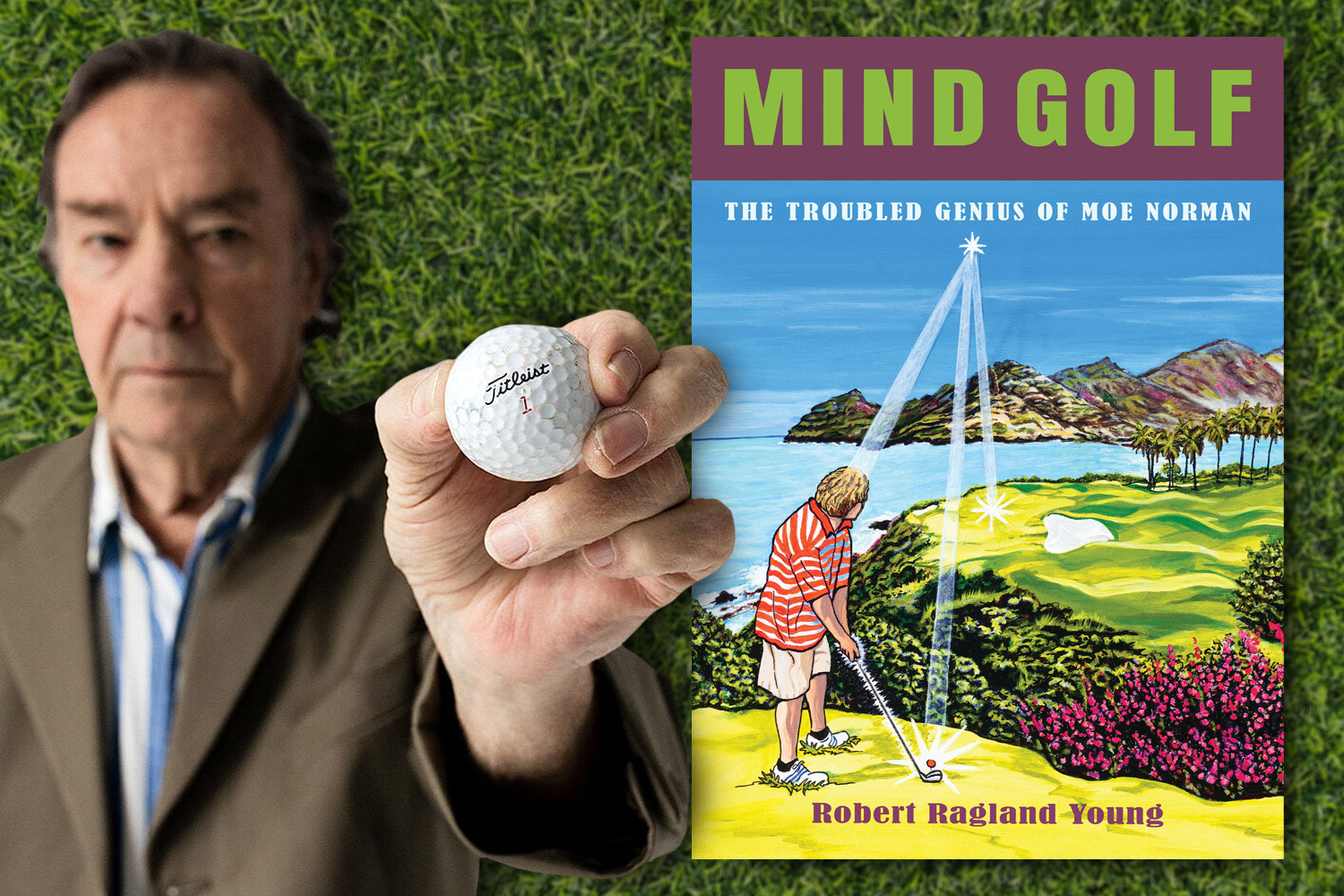

That’s Robert Ragland Young talking about his friend and mentor Moe Norman, the golfer whose unorthodox golf swing has made him something of a cult figure in the sport. Young’s new book Mind Golf: The Troubled Genius of Moe Norman, is described on its back cover as possibly being “the most unusual golf book ever written.” That’s not hyperbole — but that also seems like an approach eminently suited for the book’s subject.

Young isn’t the only voice heard in this book. Rain Man screenwriter Barry Morrow contributed a foreword in which he described his own interactions with Norman. The book’s other foreword is by one Neil Young — the author’s younger brother, who is one of three people to whom the book is dedicated.

Norman, who died in 2004, had a unique personality; both the subtitle of Young’s book and a 1995 Golf Digest article by David Owen on Norman’s life use the phrase “troubled genius” to describe him. At the time of the latter’s publication, Owen pointed out that Norman’s permanent residence was a motel room, with his clothing stored in the back seat of his car.

“To the observer, my friend Moe exhibited some of the characteristics of mild autism,” Young wrote in the pages of Mind Golf. Elsewhere in the book, he describes addressing “a serious problem with personal hygiene” that Norman had at one point in his life — something that, Young suggests, may have led to Norman being less accepted in golf circles during much of his life.

In telling the story of his own friendship with Norman, Young repeatedly returns to his observations about Norman’s achievements in golf. “He figured it out and he protected that quiet mind state in his life,” he says at one point. But Young also took a holistic approach to writing this book, observing a few times during our conversation that Norman’s approach to golf could be adopted by people in other professions as well.

“Some people think it’s magical,” Young says. “It is. Magicians could probably use this.”

“I met him when I was briefly playing, probably in an amateur golf tournament in the province of Ontario,” Young tells InsideHook about his first encounter with Norman. “He would have been more than 10 or 12 years older than I am. And he was really well known because he was so good. I watched him hit balls once in a while. And then because we played in the same tournaments, I was one of those people who tried to play good golf that he appreciated.”

Their friendship developed from there, with the two men meeting regularly to hit, by Young’s estimation, 250 to 300 balls each day. “That was in the late ’70s, early ’80s, when I first met him. The association just naturally continued,” Young adds. “I respected him. I realized he was not the same as the rest of the people.”

The consistency of Norman’s shot is what established his reputation — among both golf aficionados and some of the game’s top players, including Tiger Woods. “The observers could see that he could repeat perfect shots,” Young says. “Basically one after another, day after day, year after year.”

When discussing the contemporary state of golf — and golf discourse — Young mentions some of his reasons for writing Mind Golf. “In the last couple of years, I was watching what was going on in the PGA tour broadcasts and I noticed this thing called the shot tracker, which measures the apex, the flight of the shot and the direction it’s going in and so on,” he explains. “I kept expecting them to elaborate on some of the things that were included in the shot tracker technology, but they really didn’t do that.”

“If you read my book you’ll notice that I centered on the apex, because it’s the actual point that you choose in order to arrive at the destination,” he adds. “So what I talked about, and I use my own terminology to describe it to myself, is assembling the image of the shot to be. That has to do with energy. And Moe and I talked about that.”

Excerpt: Jason Gay Reflects on the Humbling Nature of Golf in His New Book “I Wouldn’t Do That If I Were Me”

When it comes to an enduring love-hate relationship with the game, the sportswriter and humorist is…just like usThere’s something quietly moving about certain parts of Mind Golf — Young’s use of the present tense when talking about certain memories of Norman. Norman has been gone for almost 20 years, but it gives the sense of him as a constant presence in Young’s life — and in golf in general.

But there’s also something inspiring about Norman’s longevity as a golfer, which Young brings up a few times over the course of his book. Young also seems to have taken some cues from his friend in terms of staying busy; he recorded his first single in 2020, along with members of The Sadies, as well as his brother on harmonica.

Early in our conversation, Young sounded thrilled to learn that audiobooks could be nominated for awards that he’d previously thought were only the provence of musicians. “I didn’t know this until I did it,” he said. “But you can actually be entered in the Grammys. Barack Obama read his book and won a Grammy for it.” At an age when many slow down, Young seems bound and determined to experiment with new things — something that circles back around to his time with Norman.

“The state of mind you’re in is really the foundation for what happens when you’re playing,” Young says. It’s a tenet that applies to more than just golf.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.