The beauty of science fiction is that it’s just that: fiction. We don’t always want it to come true. And yet, all too often, it does, putting the writers in the uncomfortable position of looking like prophets. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein predicted modern organ transplants. In the harrowing dystopian classic 1984, George Orwell gave us a look at mass surveillance and government control. William Gibson predicted cyberspace, social media and computer hacking in his highly influential cyberpunk novel Neuromancer. Aldous Huxley forecast the opioid epidemic in Brave New World.

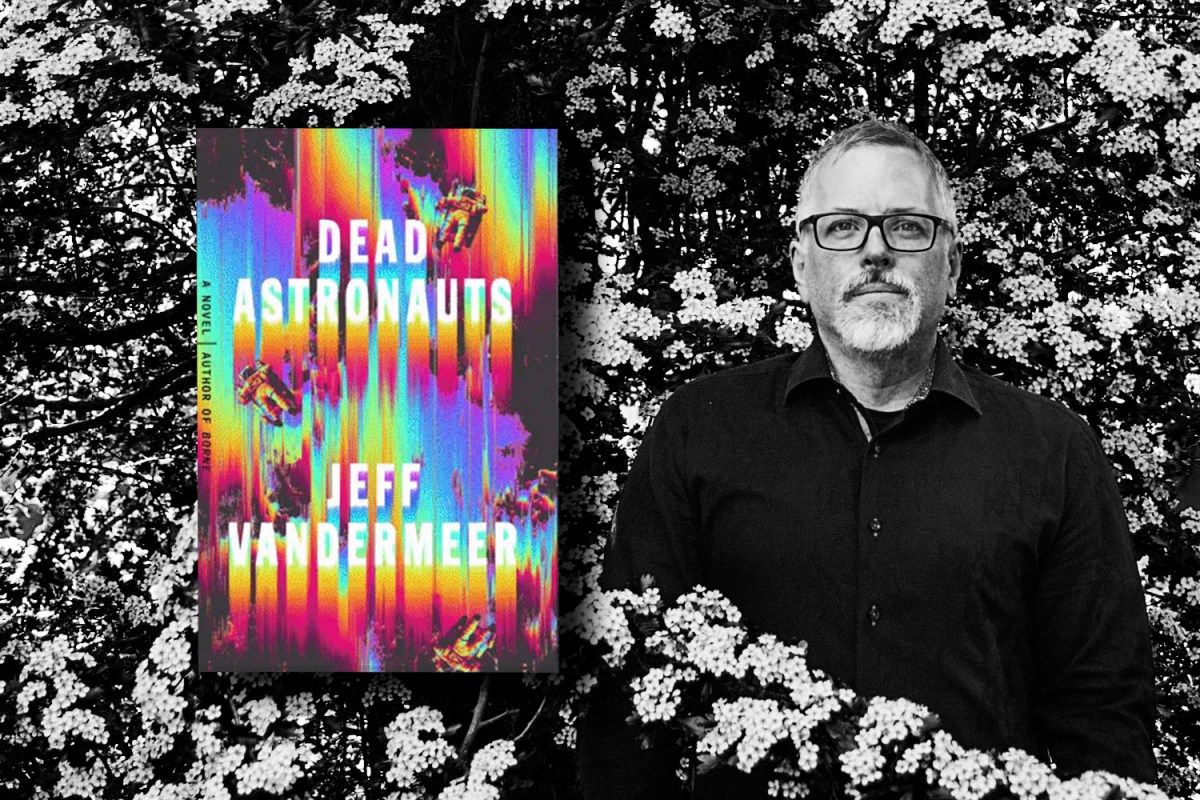

So much of what was once considered plot — the stuff of science fiction or horror — has become reality. And with our planet’s current ecological condition in a dire state, speculative-fiction writer Jeff VanderMeer’s body of work is beginning to look like the latest entry in the proud tradition of novelist-cum-oracle.

VanderMeer had been writing fiction for decades when an adaptation of his book Annihilation hit theaters in 2018. Directed by Alex Garland and starring Natalie Portman, the release represented the kind of mainstream break that most writers dreams of. But long before dreaming up Area X and nightmarish concepts like a giant flying bear named Mord, VanderMeer was part of the New Weird literary movement of the 1990s, alongside authors like M. John Harrison, Thomas Ligotti and China Miéville. The movement subverted traditional fantasy and science-fiction themes and motifs, favoring more realistic worlds to blend with the odd and the fantastical.

In 2014, the “Southern Reach” trilogy — comprised of Annihilation, Authority and Acceptance — was released just months apart by Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux. It was a risky publishing move, but editor Sean McDonald believed readers would crave more — and quickly — after reading the first volume. He was right. The trilogy landed on the New York Times bestsellers list and foreign-language and film-adaptation deals soon followed.

VanderMeer got the idea for the series while recovering from dental surgery, inspired by his frequent hikes through St. Marks Wildlife Refuge, just a short drive from his home in Tallahassee, FL. Bedridden and delirious, he had a fever dream of an oil spill spiraling up out of the ground, with living words shimmering on its surface. The rest, you could say, is history.

His latest book, Dead Astronauts, takes us deeper into the City, the setting he created for his previous two books, the 2017 novel Borne and its companion novella, The Strange Bird. The world-building in the novel is a true display of mastery: We begin with three characters hellbent on destroying the City as an act of vengeance toward the nefarious Company, which has done irreparable damage to the surrounding environment. That’s where worlds, plural, come into play, the narrative twisting and contorting to reveal the grand effects of ecological calamity. In the simplest sense, Dead Astronauts is a tale of man versus nature, with VanderMeer experimenting with narrative while probing the Big Questions: When did we, as a species, begin to drastically hurt our planet? Where’s the point of no return? And what can we do to save it?

We recently sat down with VanderMeer to see if he found any answers.

20 percent of the royalties from Dead Astronauts are going to the Center for Biodiversity and St. Marks Wildlife Refuge, the source of your inspiration for Area X, and a place I’ve been lucky enough to hike with you. It’s truly a place that feels untouched by the human footprint. Could you talk about this initiative as well as any other plans for future efforts?

The Center is the most aggressive and litigious environmental organization in the country, so it makes sense to support them as a strategic move. A lot of Trump’s worst policies regarding the environment require lawsuits to slow them down, at the very least. For St. Marks, I know they need money for their endangered salamander efforts and their work helps to understand these mysterious creatures better while also improving survival rates among young salamanders. Other efforts are mostly after I’ve finished off the next novel and have the time for more proactive activism locally. North Florida has incredible biodiversity — somewhere between 30 to 20 highest in the world. We need to preserve that against thoughtless, unimaginative development as well as nix these new “toll roads to nowhere,” which would devastate wild Florida. So there’s a lot to do here, while also thinking about how to support national and international efforts.

With every new novel, you manage a delicate balance of experimental structure and narrative. What were the motivations for weaving together such a formally experimental structure in Dead Astronauts?

In trying to write from the perspective of nonhuman animals, I felt it necessary to employ a lot of different approaches, some of them experimental. I do agree to some extent with those who say that it’s important to move beyond traditional narratives to try to convey what’s happening in this moment. That said, this was an idea I placed in the back of my head consciously — and then the expression of it was by feel and my subconscious, whatever felt natural and right, which often meant reducing the weirdness of typographical experiments. I did not, for example, want readers to have to absorb footnotes or two or three separate stories or texts on the same page. But I did think a certain kind of repetition and certain kinds of blank space, as you say, could be emotionally effective. If it’s not going to create a feeling or sensation in the reader, it’s not an experiment I’m interested in.

I’ve been reading your work since the days of Ambergris (City of Saints and Madmen, Shriek: An Afterword, Finch). Do you have plans on revisiting that world?

I have one novella, “The Zamilon File,” that’s about an expedition into the desert around Ambergris that goes horribly wrong in various temporal ways. I might finish it someday. But I think in general I wrote everything I wanted to in that setting. The only thing that might intrigue me is an autobiography of the opera composer Voss Bender, a fictional character in those novels. I’ve always wanted to attempt that as a fiction experiment in a nonfictional form. That would be very compelling.

You’re an accomplished editor, with many volumes and books ushered into publication. Alongside your wife, editor Ann VanderMeer, you’ve edited the Big Book of Science Fiction and, more recently, The Big Book of Classic Fantasy. I’d love to hear more about your experiences being an editor, and also how it has informed your work as a writer.

I’m really a novelist who also does other things, but that’s kind. I do think that reading millions of words of fiction for each of these anthologies — we’ve done something like 20 now — really helps the writing. You absorb so much so quickly and you get a real sense of what’s original and what’s just unacknowledged pastiche of prior writers. The Big Book of Classic Fantasy, in the areas we focused on animal tales, really influenced thinking about the fox’s perspective in Dead Astronauts. But, really, the editing influences all of my writing in some way.

Any writer whose work is adapted to film tends to have a very emotional reaction, just as often it’s a matter of trying to understand the reality of it. It’s been a couple years now since Annihilation entered theaters. How do you feel about it — when you first watched it versus now, after the proverbial smoke has cleared?

It got easier to watch, then harder. Now it’s impossible to watch. I mean, I don’t watch most films more than twice, so having now seen Annihilation nine times … well, nothing can hold up to that. It remains an interesting experience that I learned a lot from. The movie has a lot of amazing surreal bits. But it also has a scene in which one scientist earnestly asks another scientist whether a shark could mate with an alligator … a scene vetted by a science advisor no less. So I remain conflicted, for a wide variety of reasons. The movie sold a lot of books, which allowed me to further signal-boost environmental messages, so that was good. And I now know enough about the business that the future opportunities that are coming up … well, let’s just say I have more control and input.

What do you hope to see adapted next? Or are you more interested in writing original work for the medium?

I’m a novelist who loves to also work with imaginative creatives types. So I am happy to be serving as a creative consultant on a couple of things that haven’t been announced yet, but I have no real interest in writing teleplays or screenplays. I’d have to be an observer in a writer’s room first, and watch how something is adapted (faithfully) from my work. Then I could probably do one if I wanted to. I learn a lot through observation and mimicry. But several things are in the works. I guess you could say Ambergris is the lone fungus out, in that regard, right now.

Can we talk about what’s next on the horizon? I’m particularly excited to hear more about Hummingbird Salamander. You’ve revealed a bit about the book, how it’s taking place “ten seconds in the future,” but naturally I’m curious about what that means.

It means I can’t mention Trump or a thousand associations come in that confuse the surface of the story, but I have to convey the texture of what an era with Trump in it means to people’s lives and to our country. I finally found the right distance to comment but not be “topical,” and that’s important because the point is more generally about the era we live in, this world we live in, and issues like bio-terrorism, eco-terrorism, wildlife trafficking, and what it means to make a difference in the shadow of climate crisis. I can’t say too much because the novel is a thriller with a lot of twists and turns.

Theoretical question — If humanity were lucky enough to get a hard reset, do you feel we’d be able to avert our ecological concerns?

I don’t know what that means. There is no hard reset — we’ve poisoned too much of the planet. I understand the impulse to ask the question, but I find hypothesizing in this direction somewhat repugnant. We have this situation we have to deal with and the Earth will not return to a healthy state for thousands or millions of years. Our duty is to limit the damage and change our collective behavior and our policies — in large part by dismantling corporations and finding ways to force rogue governments to change (ours, mainland China, etc.). Threading the needle on this is very difficult, because we need to destroy many of our current systems in order to build much better ones, but among the first things to suffer during times of instability or uncertainty are both human rights and environmental regulations.

Would you like to shout out any books or authors that have been really inspiring you lately?

I’m enjoying the heck out of Vernon Subutex by Virginie Despentes. Really great stuff. I’m also quite happy with Kelly Brenner’s essays on urban wildlife, collected in the forthcoming Nature Obscura. I heard Jaquira Diaz read from Ordinary Girls at the Miami Book Fair and was blown away. Brilliant writing, brilliant reading. So that’s also high in the cue.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.