Summer is a simple novel with a simple title. It tells a simple story about simple people, and I find it absolutely gutting.

Published in 1917, Summer is often regarded — or perhaps disregarded — as the lesser of Edith Wharton’s two notable forays outside of Manhattan aristocracy and into rural New England poverty. As Candace Waid noted in a 1993 introduction to the novel, “Summer is clearly related to Ethan Frome.” Wharton herself once referred to Summer as “the Hot Ethan,” and though the work is often considered the author’s most erotic, it tends to get overshadowed by the literary legacy of its frigid counterpart.

To be fair, it didn’t take much to render a book shockingly erotic at the time. Summer is hardly the kind of sexy beach read we know today. The sexual awakening of its heroine, 18-year-old Charity Royall, is necessarily veiled — however exquisitely — in figurative descriptions of “the long flame burning her from head to foot” and “the wondrous unfolding of her new self, the reaching out to the light of all her contracted tendrils.” Aside from a handful of kisses and embraces, the most overt references to sex in the novel actually depict its absence: a failed intrusion into Charity’s bedroom, and a new husband sleeping alone in a chair by the bed of his much younger wife on their wedding night.

At face value, Summer is a typical tale of summer love, following the predictable “loss of innocence” narrative to which most literary depictions of female sexuality were obliged to conform at the time: young woman falls in love, has sex, is punished for it. Progressive readers today may find themselves disappointed in the villainous characterization of the abortionist or the apparent sense of salvation through sacrifice Charity seems to find in the idea of motherhood.

But Summer is many things. It is a tale of sex and sexism, of rural poverty and the class stratification that still manages to emerge within it, of loneliness, incest and, as Wharton put it in A Backward Glance, “the slow mental and moral starvation … hidden away behind the paintless wooden house-fronts” of decaying rural communities.

Summer is all these things. But for me, above all else, it has always been a book about endings.

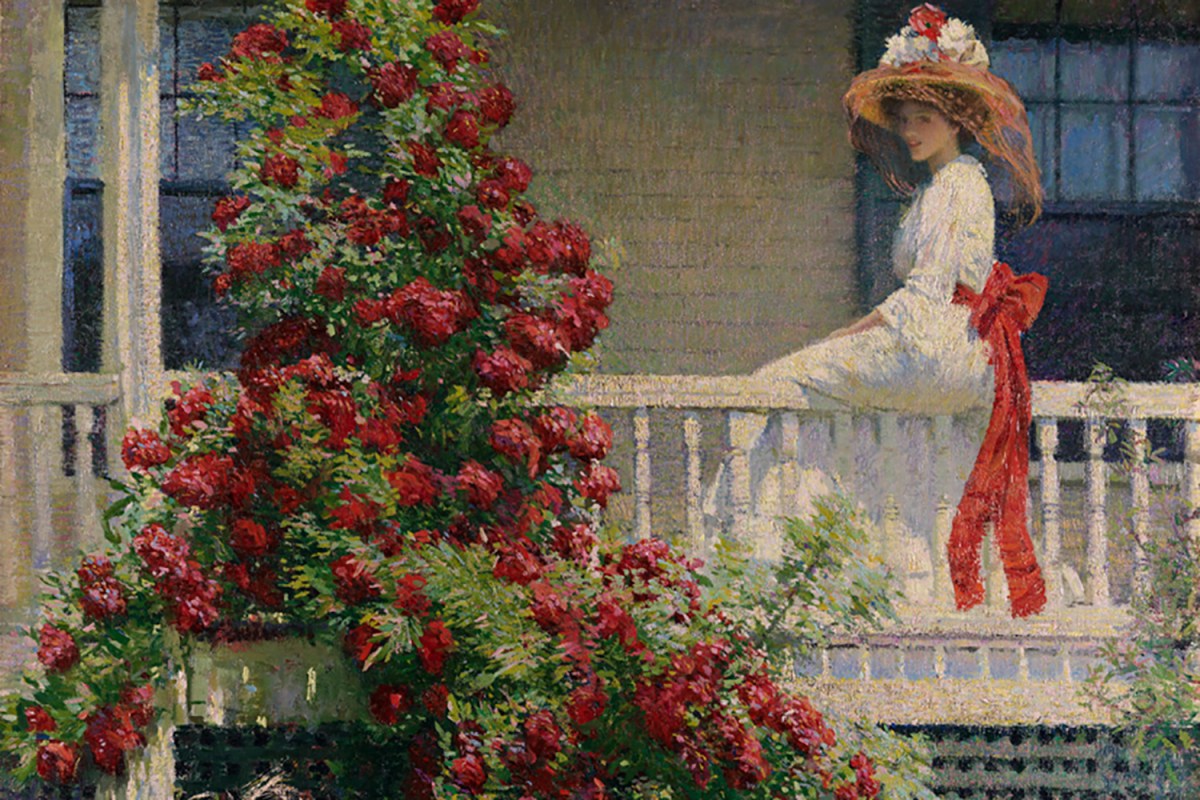

Like most tales of summer romance, Wharton’s is weaved predictably within the arc of the season. Charity first emerges onto the porch on a sunny day in June, has her first kiss under a shower of July 4th fireworks, and eventually finds herself resigned to her fate beneath the “cold autumn moonlight.” But somewhere in between the midsummer loss of innocence and the inevitable autumnal punishment, Wharton manages to capture another, less obvious seasonal shift and the corresponding psychic rupture it portends.

The last time Charity meets her lover in the abandoned house they’ve made into their summer love nest, we are told it is a “sultry” late summer afternoon, but by the time they leave, an irrevocable shift has occurred:

“The last glow was gone from behind the Mountain. Everything in the room had turned grey and indistinct, and an autumnal dampness crept up from the hollow below the orchard, laying its cool touch on their flushed faces.”

Here, Wharton has captured what is usually an unspoken, almost imperceptible moment: the beginning of the end — the moment we first realize something is over before it is, when we see the end coming and pretend we didn’t. Summer isn’t over yet; mere hours earlier Charity was forced to take refuge from the sweltering weather, and weeks later she steps off the train to the abortionist’s office into heat we’re told almost rivals the Fourth of July. The lovers themselves don’t know this will be their last meeting; in fact, they promise each other the opposite. And yet, something is over. With the cool kiss of autumnal chill, however brief, something irreversible has happened.

I am obsessed with these moments, in life as in literature, these endings before the endings. They’re clearer in retrospect, of course, when we go back through our minds clawing desperately for answers, for the what went wrong. But I think we know when they happen, on some level. Deep down, some part of the psyche registers an otherwise imperceptible shift in those few seconds of silence over brunch or a stray vacant look in a lover’s eyes that brings a sudden flash of, “Who are you? Have I ever known?”

These moments can strike anywhere at any time, and when they do, they are usually fatal. Nothing has happened, not yet, but somehow this is the end. Some illusion has fractured; soon it will shatter.

In these moments, we know before we know, the same way we know that stray cool morning or evening in late August. There may be weeks left of summer, seemingly endless days left of sweltering heat and sweaty, sleepless nights. But there is something irrevocable in the unexpected chill of that first cool morning, when the gauzy green dress you’ve worn all summer leaves you shivering on the morning-after walk home from a stranger’s apartment. By noon you know you’ll be sweating through it again; there will, as Charity’s lover promises in vain on what is ultimately their last meeting, be more and better days ahead. And yet, something is different. Some fantasy or other has vanished. Something has ended. Summer is gone.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.